Immersion in a home visit: when support strengthens the care pathway

The RAITRA project aims to improve the health of vulnerable populations in Madagascar by strengthening the prevention of tuberculosis, HIV and malaria, while integrating community actors into national strategies and empowering local NGOs.

Tuberculosis thrives where extreme poverty and malnutrition weaken immune defences. In the deprived districts of Antananarivo, Madagascar, tuberculosis remains a silent shadow: despite free treatment, 8.5% of diagnosed and notified patients were lost to follow-up nationally. Poverty, malnutrition and stigmatisation — extremely precarious living conditions — hinder access to care.

In this context, the RAITRA project, supported by L’Initiative since July 2021, focuses on including disadvantaged urban communities in TB screening and care. It relies on a network of community actors and the empowerment of local NGOs to strengthen prevention of tuberculosis, HIV and malaria by building trust with patients to remove psychosocial barriers and ensure optimal adherence to treatment protocols.

Immersion in a home visit, a true pillar of this innovative scheme.

Immersion in the RAITRA project

RAITRA’s mission is to involve these vulnerable communities directly through a strong partnership between ATIA and three local NGOs: KOLOAINA, VAHATRA and MAMPITA. Since July 2021, community actors have been touring deprived neighbourhoods, not only to deliver medicines but to listen, talk and co-design tailored support. Their credo: put the person back at the centre of care.

t is 2:00 pm in the western part of the Analakely district of the capital: under the corrugated-iron roof of a small wooden dwelling, a young mother in her twenties — whom we will call Miary — tries to rock her recently circumcised baby. Visibly emaciated, she complains of severe abdominal cramps and persistent pain when she tries to swallow a few mouthfuls of rice. Every sip is an ordeal.

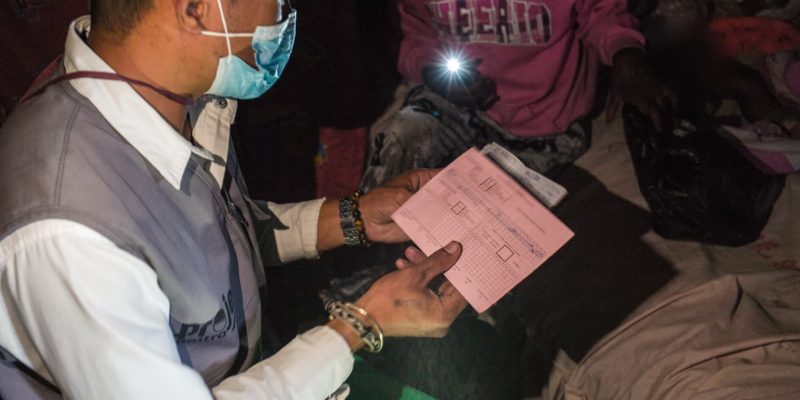

Faly, a community health worker from partner NGO KOLOAINA, sits on a bench by the bed, close to her, and begins with a reassuring smile: “Miarahaba anao, Miary. Thank you for welcoming me. Tell me how you are feeling today.” Gradually the young woman’s face relaxes: she explains that to collect her medication she must cross makeshift bridges over polluted ponds and then walk for a long time under a merciless sun — a journey impossible when one has neither strength nor resources.

Faly takes notes and asks open questions to understand the root of her distress: fear of infecting her child, shame in front of neighbours, the disease eating away at her body. He listens without judgment, offers hygiene and nutrition advice, and reassures her that her treatment must not be interrupted. He encourages her and looks for ways to help: “It is essential to continue your treatment until the end. Can you ask your husband to come and collect your medication for you?”

As the conversation unfolds a bond of trust forms: Miary accepts sharing her fears and senses that people care about her wellbeing. Before leaving, Faly offers to return to her home within a maximum of fifteen days. On his way back he is already noting the referral points to mobilise so that no question is left unanswered.

Methods that make a difference

Each home visit is built on a structured approach: active listening, motivational interviewing and supportive counselling. Community health workers are trained to detect gender-based violence (GBV), to provide individual awareness-raising and to refer patients to other services (hospitalisation, nutritional support, legal assistance). In parallel, twice a month support-group workshops bring patients and their supporters together to break isolation and lift self-censorship. Each week a weekly clinic is held at the diagnostic and treatment centres. This holistic approach creates a true safety net around patients.

Thanks to this strategy the lost-to-follow-up rate has fallen dramatically: just 0.56% within the RAITRA project, compared with 8.5% nationally. Screenings increased by 25% in the targeted neighbourhoods, and patients report renewed confidence in the health system.

Since then national authorities have recognised the effectiveness of this approach, complementary to the work of community health workers. Buoyed by these successes, local organisations are calling for a national scale-up of this psychosocial support model. They state that by integrating these home visits and social clinic hours into the public health framework, Madagascar could transform its TB response sustainably and drastically reduce losses to follow-up.

By complementing clinical care, RAITRA shows that the fight against tuberculosis is not confined to dispensaries: it is reinvented in patients’ everyday lives through home visits, kind words and acts of solidarity that change the course of illness.