“We really advanced blindfolded” — Understanding the care pathway for survivors of sexual violence in Madagascar

A public health physician and recipient of the Françoise Barré-Sinoussi Excellence Scholarship supported by L’Initiative – Expertise France, Dr Sedera Rakotondrasoa carried out a study on the care pathway for survivors of sexual violence in the Analamanga region of Madagascar. His work highlights concrete obstacles — silence and self-censorship after trauma, fragmented services and indirect costs — and proposes practical solutions to make services more accessible.

Can you introduce yourself?

Dr Sedera Rakotondrasoa: I am a public health physician. In the field I coordinate communicable disease control programmes in a health district in the Analamanga region of Madagascar. My research focuses on HIV, maternal and child health, tuberculosis, viral hepatitis and neglected tropical diseases. I am particularly interested in the most vulnerable populations, notably women and children.

What is the aim of your study and why did you undertake it?

Dr Sedera Rakotondrasoa: My study analyses the real-world care pathway of survivors of sexual violence in the Analamanga region.

I chose this subject because sexual violence affects about 13.7% of women — an alarming figure that in fact conceals an even graver reality because it is widely under-reported. In my work I observed that many peripheral healthcare providers hesitate to manage these cases, often out of fear of medico-legal implications, while survivors, especially in rural areas, struggle to access essential care such as prevention for sexually transmitted infections and HIV.

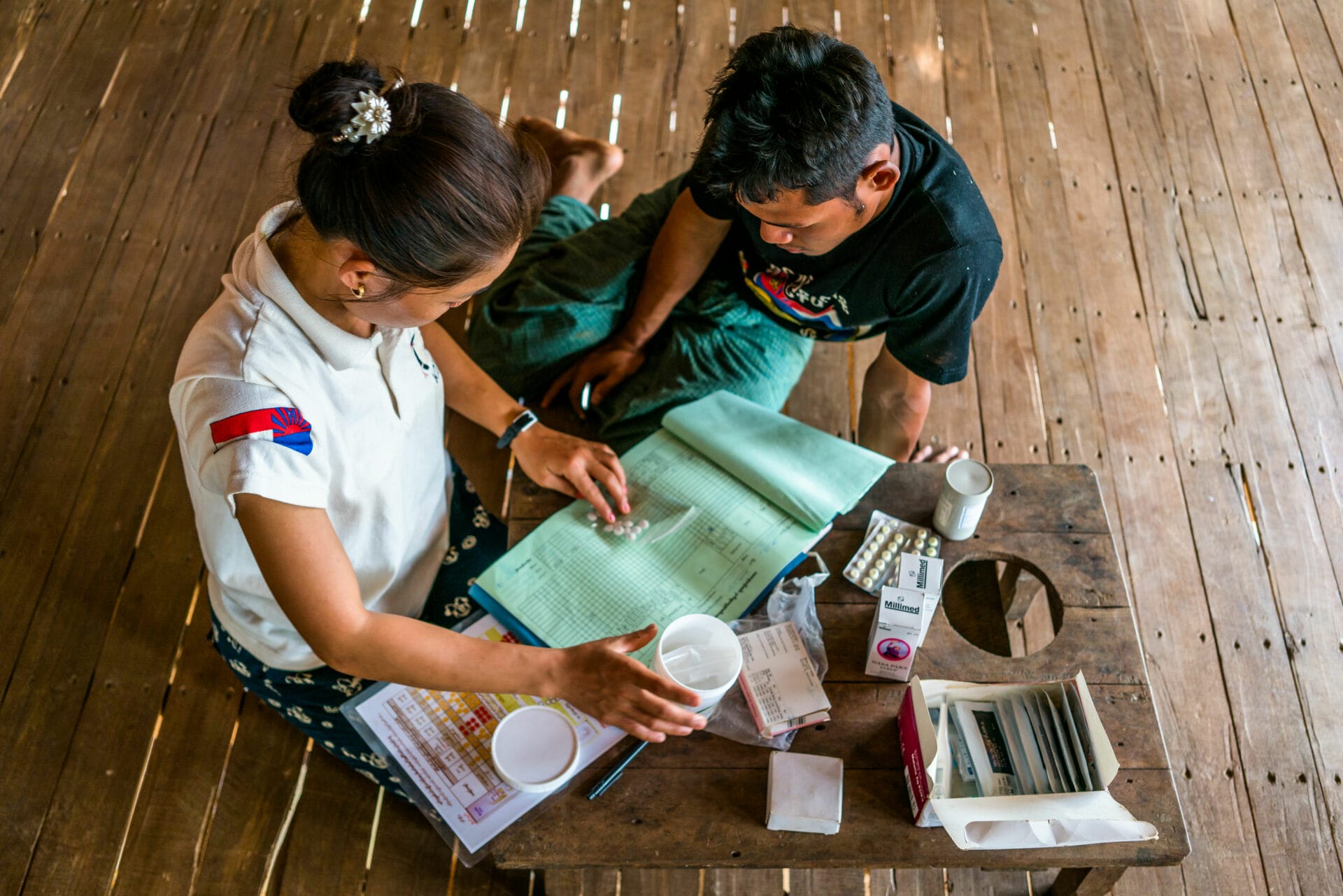

Faced with this fragmentation, the Centre Vonjy represents a model of excellence by bringing all essential services together — clinical care, psychological support and legal accompaniment — under one roof. But is this centre truly accessible to the survivors who need it most? I wanted to understand the gap between the ideal model and field reality, and to identify the concrete bottlenecks in the system.

What are the main findings of your report?

Dr Sedera Rakotondrasoa: Three findings seem crucial to me:

First, initiation of the care pathway: many survivors do not dare take the first step — paralysed by trauma and the fear of judgement. The system must reach out to them, with accessible entry points within communities.

Second, fragmentation of the pathway: survivors navigate between poorly articulated services and have to repeat their stories, which is exhausting; the challenge is to create clear bridges between actors.

Finally, financial accessibility: even where care is nominally “free”, indirect costs (transport, certificates, tests) remain major barriers for the poorest.

I still have in mind the case of a woman in her forties living in a remote Malagasy village. After being sexually assaulted, she sought help only three months later. Shame paralysed her; fear of rumours kept her from acting. She did not know that emergency medical care is available within 72 hours — notably to access post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for HIV — nor that specialised centres such as Centre Vonjy exist. She also believed that a consultation would cost 10,000 Ariary (about €2), a sum she did not have. When the pain became unbearable, she knocked on several doors. A local official requested a paid medical certificate. At the district hospital she was told that there was “no proof”, that too much time had passed since the assault. It was finally a gendarme and then a public prosecutor who took the time to listen to her and referred her to Centre Vonjy. To get there she had to borrow money for transport. At the centre, the touted free care collided with the reality of insufficient equipment. She was sent from one hospital to another for tests, forcing her family to make unplanned payments totalling 100,000 Ariary (around €20).

Was the Françoise Barré-Sinoussi Excellence Scholarship decisive for your work?

Dr Sedera Rakotondrasoa: The scholarship was crucial. I had the honour of being awarded this prestigious Excellence Scholarship, a selective programme funded by L’Initiative – Expertise France. It enabled me to follow the Master 2 (M2) “Global Health in the South” course in Bordeaux and to carry out this study in Madagascar. Practically speaking, the scholarship was the key that made everything possible: it covered my training, the field logistics and, importantly, ensured impeccable ethical conditions by allowing me to compensate participants for their time and expenses.

Professionally, it gave me legitimacy and research methods; personally, it confirmed my career project. The results are concrete: a report with directly usable recommendations and the prospect of scientific publications that will make a lasting contribution to research on this topic.

What operational follow-up do you recommend?

Dr Sedera Rakotondrasoa: My report proposes a detailed roadmap, but if I had to stress priority actions they would fall into three levels.

For decision-makers: make the system proactive and coordinated — implement an official protocol among Ministry of Health, police and the Centre, and a shared monitoring tool to avoid institutional “ping-pong”.

For NGOs and field actors: step up awareness about the 72-hour window and create emergency funds to cover transport and administrative fees.

For practitioners: adopt a compassionate listening approach and promptly and clearly refer survivors to the nearest specialised service.

This report does more than describe the problem: it analyses in depth the causes of system fragmentation, drawing on testimonies from survivors and professionals. It offers a clear, practical roadmap to turn intentions into concrete actions.

I wish to express my deep gratitude to the survivors who shared their stories. Their courage fuels this work. My sincerest hope is that this study, albeit on a small scale, will contribute to ensuring that fewer and fewer survivors of sexual violence ever have to say: “We really advanced blindfolded.”