Climate change and health surveillance systems

Integrating indicators of environmental dynamics and climate change into health surveillance systems is a long-term effort—one that Florian Girond is dedicated to. A health geographer, he supports the Communicable Disease Control Department (CDC) within Cambodia’s Ministry of Health. He models health and environmental data and makes them accessible through interactive digital platforms. The goal: to improve health responses through better understanding of climatic factors. He also shares a project he is conducting, based on a One Health approach, to better respond to dengue in the country.

How did you come to work with Cambodia’s Communicable Disease Control Department (CDC)?

Florian Girond: Before joining the CDC, I was already working in Cambodia, particularly with the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (IRD) and the Institut Pasteur du Cambodge (IPC). During the COVID-19 crisis, we supported the Ministry of Health by developing data pipelines that linked epidemiological data to laboratory data from the IPC. In 2022, I joined the CDC—as an international technical expert (ITE)—which aims to monitor and respond to epidemics. My work focuses in particular on communicable disease surveillance. I place special emphasis on the environmental and climatic dimensions, in order to build forward-looking, iterative early warning systems.

What is the context in Cambodia on these topics?

Florian Girond: Cambodia has set up a digital syndromic surveillance system (DHIS2). It allows tracking of several diseases based on a group of symptoms, including those associated with dengue, encephalitis, respiratory infections, or meningitis. This system is part of an early warning framework capable of detecting unusual increases in case numbers or breaks in time series—that is, abnormal trends in the data.

Together with IRD, and especially Vincent Herbreteau from the ESPACE-DEV joint research unit (UMR), we are exploring how to integrate environmental dynamics and climate change indicators into surveillance systems. By combining environmental and climate variables obtained via satellite-based remote sensing with health data, it becomes possible to model the progression of an epidemic by linking it to an external factor. For instance, a rise in dengue cases may be linked to anomalies in rainfall or temperature in the preceding weeks. We need to “feed” health surveillance systems—by adding explanatory data to improve the predictability of future alerts and make it easier to contextualize and interpret warning signals. What is happening today enables us to make longer-term forecasts (8 to 12 weeks) and to establish a prospective, operational model.

How are these data used?

Florian Girond: For the data to be fully exploited, they need to be visualized. We are developing interactive platforms that allow users to observe how case numbers evolve over time, in a chronological way, but also geographically. As a health geographer, the spatial aspect of analysis is essential to me.

We use tools like R, an open-source programming language that allows statistical processing and graphic visualizations. We train the country’s health and environmental authorities in how to use these tools. This gives them immediate access to the available data. For example, they can detect a peak in dengue cases in a province and link it to climate data (rainfall, temperatures, long-term anomalies).

We also produce interactive dashboards and weekly epidemiological bulletins, adapted to each province’s context. The goal is for provincial health authorities to quickly detect a signal, track the situation’s evolution, and take appropriate decisions for population’s health. One of the key challenges—and what we’re working on with IRD—is integrating accurate climate data, due to the shortcomings of the existing meteorological network. We’re also working to remove the technical and methodological barriers that prevent health actors from accessing environmental and climate data from satellite sources.

The ultimate goal is to adapt detection thresholds to the country’s response capacity, so that the necessary resources can be allocated to contain epidemic risks. That’s why it’s important to take a forward-looking approach, publish weekly epidemiological reports, and train the relevant stakeholders, so that the information shared can actually be useful to health authorities.

Could you tell us more about the Comprehensive Integrated Surveillance and Early Detection System for Dengue (CISED)?

Florian Girond: Through the CISED project, we are working to strengthen dengue epidemiological surveillance and improve early detection of this viral infection. It’s a major health issue in the country, especially after several successive epidemics in recent years. Dengue is a good example of a disease that is particularly sensitive to climate changes, among other factors: variations in temperature and rainfall dynamics affect the mosquitoes that transmit the disease.

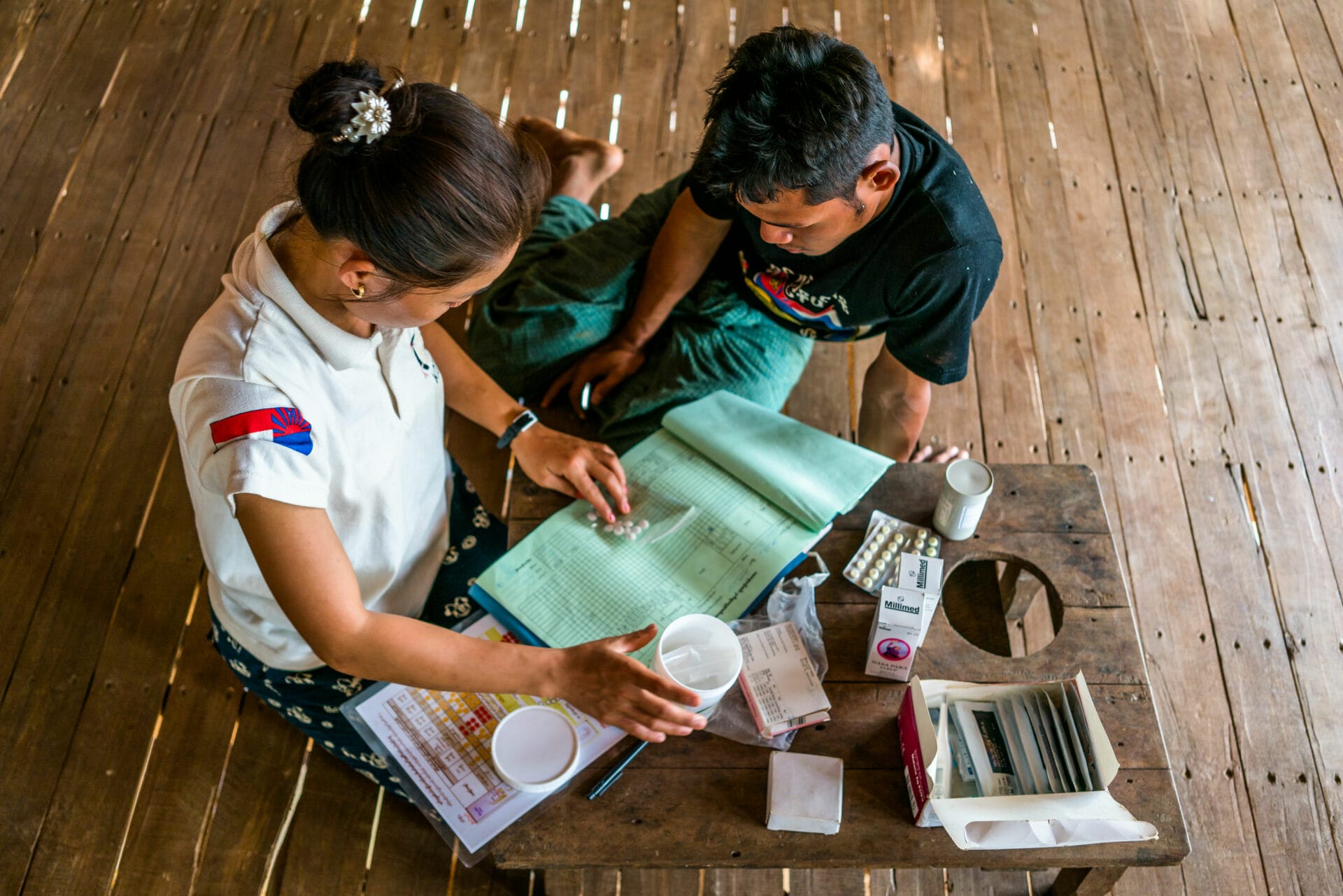

Monitoring dengue virus circulation requires integrated, multidisciplinary surveillance approach. This is why the project brings together a broad range of actors involved in the surveillance of this infectious disease. The goal is to build on a collective reading of the data to anticipate epidemic waves and enable early detection, in line with a One Health approach.

Via a public platform, verified information and clear messages are shared with the population in real time, including risk alerts and prevention tips. For dengue, based on already available data and climate change indicators (such as environmental anomalies or identification of extreme events), we are now able to predict outbreaks twelve weeks in advance.