Greater Mekong: the “double burden” of middle-income countries

In the Greater Mekong Subregion, countries face major public health challenges: combating increasingly prevalent non-communicable diseases and pursuing the goal of eradicating pandemics. To make these ambitions flourish, international assistance is essential.

On June 10 and 11, L’Initiative is organizing regional meetings in Bangkok to discuss with its partners the issues related to the fight against pandemics in Southeast Asia and to create synergies between the main players in the area.

On this occasion, Patrice Piola will return to the health issues in the Greater Mekong sub-region, which he knows well. This area brings together Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam, countries with diverse histories and modern realities, which today face a common “double burden” of public health, combining pathologies from developed and developing countries.

This epidemiologist draws on 25 years of experience (notably at Médecins sans frontières and the Pasteur Institute) in medical program management and operational research. He recently coordinated a research program on malaria in forest areas in Cambodia, with the support of L’Initiative.

What are the public health issues common to the Greater Mekong countries?

In terms of public health, these are middle-income countries, with a more urbanized population than before. Non-communicable diseases such as cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases are now the most deadly. They affect nearly 60% of the population, a rate close to that of the most developed countries. However, the problems of developing countries remain significant: access to care, particularly in rural areas, maternal and child health, and infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, malaria, and HIV-AIDS. There is talk of a “double burden” of public health for these countries, which must fight against both types of pathologies – which sometimes aggravate each other, such as diabetes and tuberculosis. Added to this is a third major challenge: pandemic preparedness.

How do these countries have a key role to play in pandemic preparedness?

The Greater Mekong region has a colossal wealth of biodiversity, which is being undermined by climate change and urbanization. This situation constitutes a favorable melting pot for diseases such as avian flu and Covid, but also the Zika virus, chikungunya and dengue fever. Thailand has a very efficient diagnostic and laboratory network, which places it at the forefront of detecting emerging diseases. However, international aid remains essential to support it and help other countries in the region to progress.

If non-communicable diseases are today the main factor of mortality, should we focus on infectious diseases such as malaria, HIV-AIDS and tuberculosis?

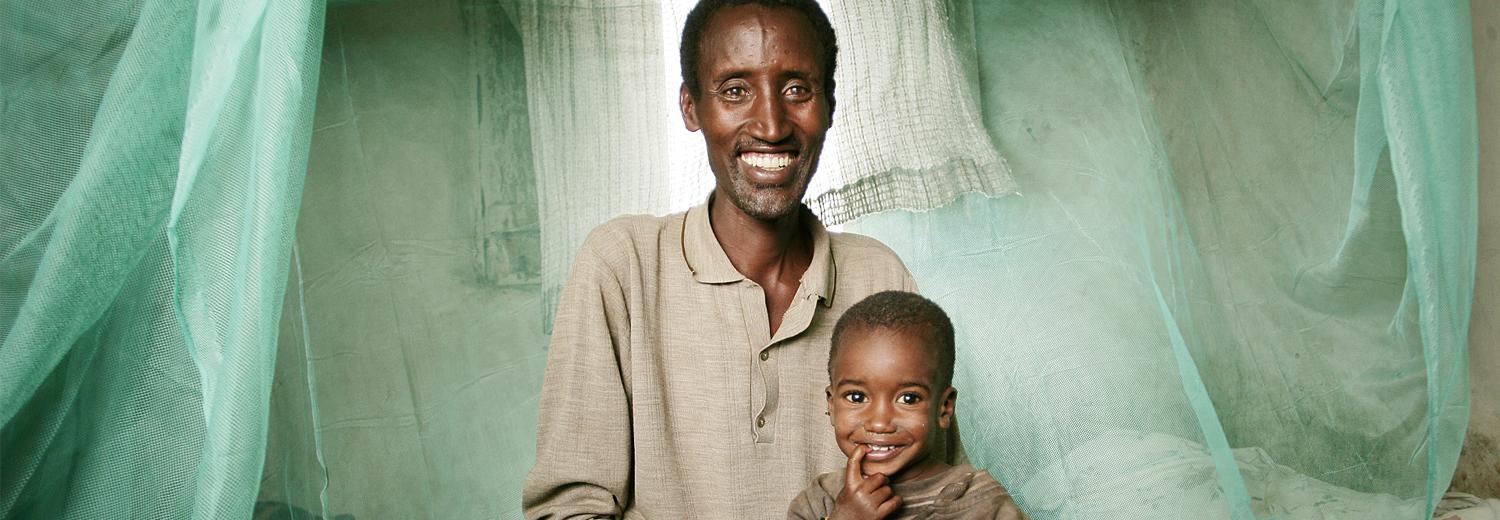

We are seeing the fruits of the immense efforts made in recent years. Malaria, for example, now kills only about ten people per year in the Greater Mekong region. But the region has seen the emergence of almost all the resistances to antimalarial drugs, to chloroquine and fansidar in the 1950s and 1970s and more recently to artemisinin. This resistance could wreak havoc if it spreads to countries hardest hit by malaria in sub-Saharan Africa. The international will is therefore to “finish the job” and simply eradicate malaria in the Greater Mekong region, in order to see the end of the colossal efforts that have been made.

How to achieve this?

Generally speaking, we need to get as close as possible to the populations most at risk. For malaria, these are those living near forests. We need an extremely sensitive surveillance system to respond to the first reported case: identify the village and ensure that the entire population concerned is tested, or even treated, so that no one catches malaria and transmits it, at the risk of the disease, which is declining in the region, regaining momentum.

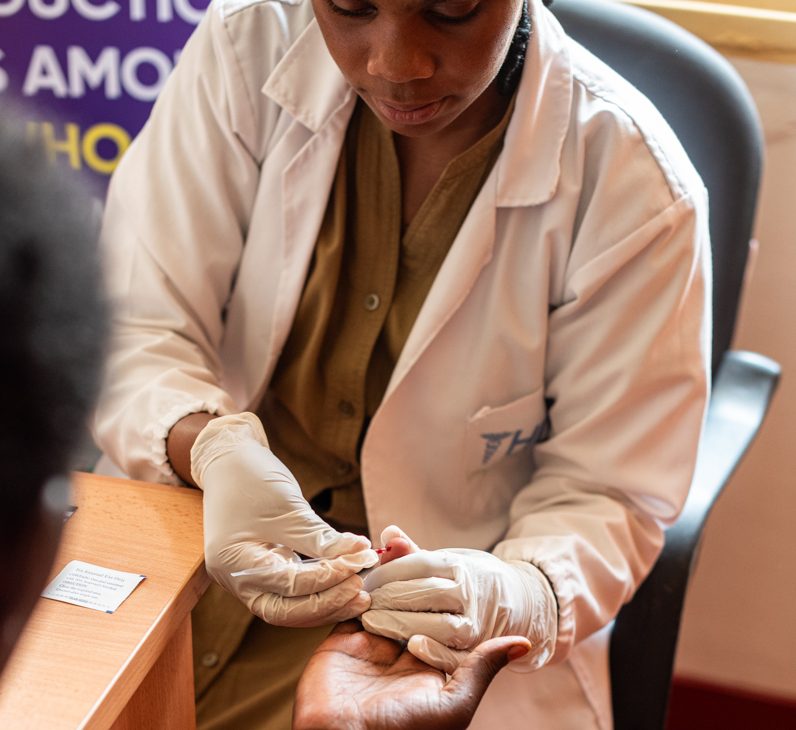

For tuberculosis, the populations most at risk are the poorest, children and the elderly, prisoners, migrants and people living with HIV/AIDS. Screening in these populations is necessary to treat each case.When it comes to HIV/AIDS, the groups most at risk are sex workers, men who have sex with men, transgender people and injecting drug users. We must be there to inform and prevent them, diagnose them and treat them. Testing all pregnant women is also essential to prevent any transmission to the child.

Setting up an effective surveillance and control system is possible, but it relies on a network of doctors, caregivers and laboratories, in the vicinity, as close as possible to the population. It requires well-trained doctors to detect the clinical signs of each disease, laboratories to conduct the tests and information systems to report the data at the national and international level.

How to achieve this?

The needs are similar but each country is at a different stage. Thailand now has a high-quality health system. Vietnam, which is experiencing very rapid economic development, is strengthening its health system, particularly in rural areas. Cambodia and Laos are making progress, but still need support to strengthen their networks of hospitals and health centers. Myanmar is a special case, which is facing a deterioration in its health situation, due to the political context.

The common challenge for all these countries is to ensure access to care for the entire population – particularly in rural areas – with an effective network of large regional hospitals, local health centres and community workers. It is therefore necessary to train enough doctors and healthcare workers and distribute them throughout the territory with adequate equipment and reliable laboratories. Community workers play a vital role in the most isolated villages, so their correct remuneration is essential.

What phenomena could call into question access to care for all?

Price. Indeed, fair access to care is important. Thailand – and to a lesser extent Vietnam – has such high-quality health infrastructure that the country is now experiencing a phenomenon of medical tourism, with private care that is certainly cheaper than in Europe, but inaccessible to the majority of the population. A free, quality healthcare offer that is accessible to people in rural areas is essential. This has a significant cost for a Ministry of Health and international aid therefore remains necessary.

In the context of the fight against HIV-AIDS and tuberculosis, as in the context of mental health problems that are still taboo in the region, it is necessary to combat the stigmatization of patients: people who are ashamed of their illness may not dare to seek treatment and thus spread it further. Here again, the work of community workers is key to getting essential messages across.

What can international aid do to best support these countries?

We are seeing today that international aid tends to be redirected to other countries with more pressing needs, leaving the Greater Mekong countries to arbitrate when the share of aid decreases. However, the countries in the area, particularly Cambodia and Laos, still greatly need help so as not to lower their guard in the face of major pandemics. The idea is not to replace the Ministries of Health of the countries concerned, but rather to conduct pilot projects, as we did, with the support of L’Initiative, on malaria in forest areas in Cambodia. We highlight a problem, by proposing a preventive and therapeutic approach, and if it works, we propose to the government to deploy it on a larger scale. As a field doctor, this is how I feel useful.

Do non-communicable diseases and pandemics still require other means?

Yes, the most innovative treatments for diabetes, cardiovascular diseases or cancer are very expensive, often out of reach for these countries. When pandemics like Covid require sending people to intensive care, skills and equipment are also required that are very expensive. The Greater Mekong countries must therefore arbitrate with a per capita health budget well below the world average.

Can we use new technological tools to advance research and access to care?

Telemedicine and artificial intelligence can be excellent tools to aid diagnosis, especially in the most isolated rural areas: qualified doctors are sometimes far away, but the Internet is available almost everywhere, so we might as well take advantage of it. From a One Health perspective, technologies are also very useful for strengthening the circulation and analysis of data between different professional groups (veterinarians, ecologists and doctors) and thus identifying the factors that promote the emergence of diseases. This is a crucial issue, which most ministries do not really have the time to deal with and which the international community could help to develop.