Against HIV, PrEP protects the most vulnerable

For individuals particularly exposed to HIV, pre-exposure prophylaxis, commonly known as PrEP, is a proven prevention method. This treatment almost completely reduces the risk of infection. The “PrEP Femmes” project promotes the deployment of PrEP among sex workers in Morocco and Mali, as well as transgender women and partners of people who inject drugs in Mauritius. Dr. Lahoucine Ouarsas outlines the key issues of the project.

What is the purpose of PrEP?

Dr. Lahoucine Ouarsas: The condom remains the primary protection tool against HIV, but for some individuals, it is not enough. PrEP is an antiretroviral medication prescribed to HIV-negative people to help them stay negative. For example, sex workers may not always have the ability to enforce condom use with their partners. We offer PrEP to the beneficiaries of our HIV/AIDS prevention association (ALCS) in Morocco, alongside a range of prevention tools, so they can choose what best suits their situation.

How does your association work with sex workers in Morocco?

Dr. Lahoucine Ouarsas: It is estimated that there are around 75,000 female sex workers in Morocco, and we are in contact with half of them. Some come to our fixed structures, clinics, and testing centers. We can also reach them through our mobile units or via community relays, who carry prevention kits to certain places they frequent. Some of them actively participate in our activities and the development of our strategies; they can become peer educators.

As part of the combined HIV prevention approach, we focus on three areas. The first—the behavioral approach—addresses issues such as negotiating sexual relations or building self-esteem. The second is the biomedical approach, which includes care, testing, and the management of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Finally, the structural component aims to improve their social situation and empowerment.

How was the “PrEP Femmes” project developed?

Dr. Lahoucine Ouarsas: PrEP is now a recommended prevention method for populations particularly vulnerable to HIV. In Morocco, our association launched a first pilot project on PrEP in 2017, targeting sex workers and men who have sex with men. This initial project was positively evaluated and expanded. However, we noticed that women were using PrEP less than men, and we are trying to understand why. Our goal is to understand the determinants of this underuse and conduct a solid scientific study. Based on this data, we aim to build a service that better meets the needs of the women involved and advocate with policymakers to remove barriers to PrEP uptake.

Between 2020 and 2024, the first phase of your study on the distribution of PrEP to key populations was supported by L’Initiative. What barriers to PrEP uptake have you identified?

Dr. Lahoucine Ouarsas: First of all, taking medication continuously when one is not sick is not easy to accept. Moreover, the pill form of the treatment causes unpleasant side effects (stomach pains and nausea), especially at the beginning of the treatment. Some people have also expressed concerns that others might find out they are taking the treatment and assume they are HIV-positive. Even having the box of medication at home can pose a problem. Finally, some doctors are reluctant to prescribe PrEP, fearing it might contribute to HIV resistance to treatment. Therefore, there are a number of sociocultural barriers to overcome and misconceptions to address, in addition to the real challenges of the treatment itself.

How can we address the costs of these treatments?

Dr. Lahoucine Ouarsas: We are working with the beneficiaries to find ways to overcome these social barriers. Some have suggested changing the way the treatment is taken. There are options in injectable form, as a vaginal ring, or combined with oral contraceptives. During this second phase, we will specifically test the acceptability of the injectable PrEP. Women are also requesting better support to improve their negotiating power during sexual intercourse so they can enforce condom use and avoid violence.

Why could injectable PrEP be a good solution?

Dr. Lahoucine Ouarsas: This form would allow women to no longer have to remember to take their pills every day while staying protected for several months. There are injectable PrEP formulations, such as cabotegravir, which provides protection for two months. We hope that soon lenacapavir, which has so far been reserved for HIV treatment, will be available, as it provides protection for six months and is administered subcutaneously—making the injection less painful. The downside is that the cost of these medications makes them inaccessible: $20,000 per person per year for cabotegravir, and $40,000 for lenacapavir.

You work in partnership with associations in Mali and Mauritius. What is the value of international cooperation on this project?

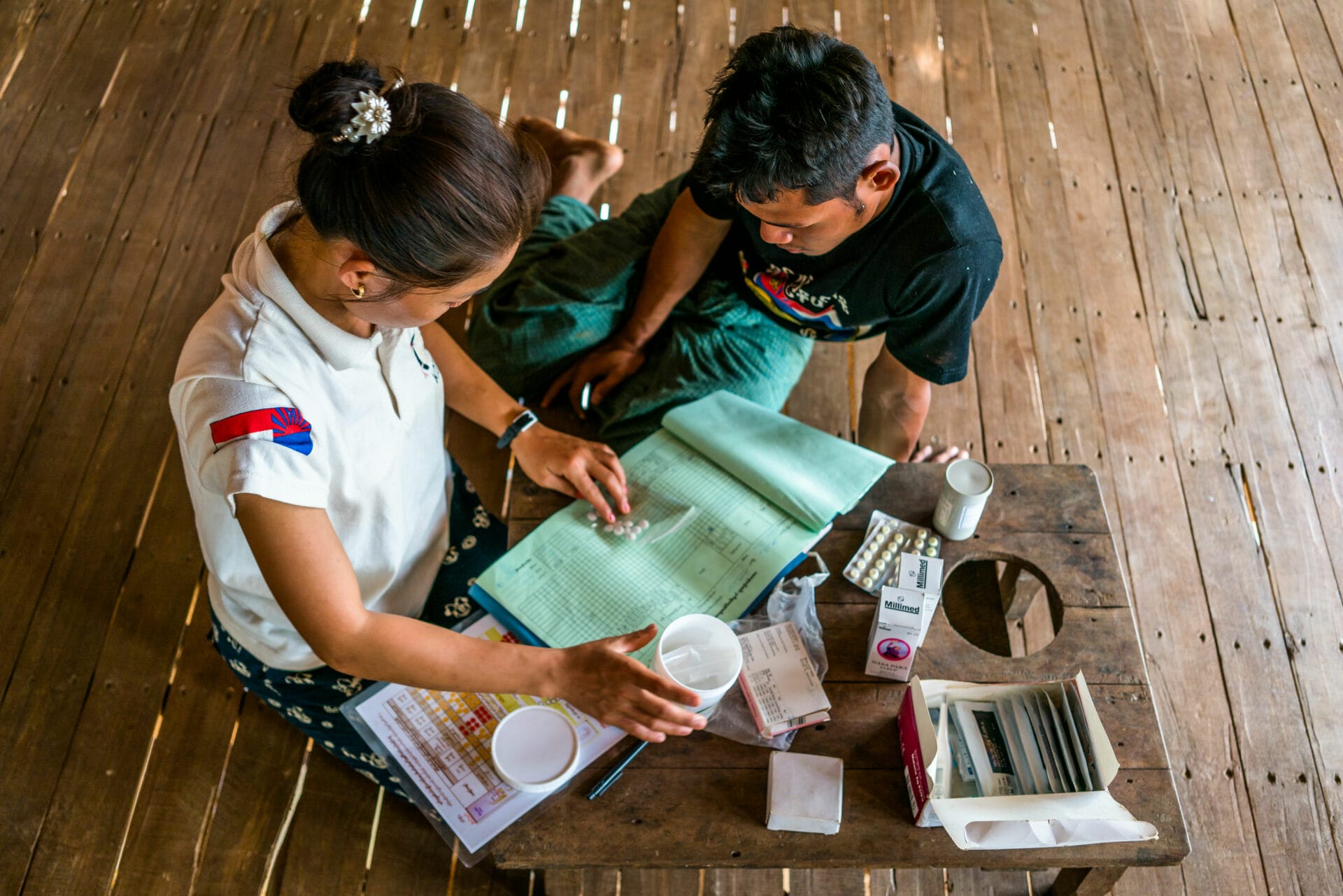

Dr. Lahoucine Ouarsas: Sharing expertise and best practices is fundamental. Since May 2020, we have been cooperating with ARCAD Santé Plus, which works with sex workers in Mali, and with PILS, which promotes PrEP among transgender women and partners of people who inject drugs in Mauritius. In Mauritius, there was only a hospital-based solution, with no community-based offer. We went to present the results of the first phase of our study and convinced them to change their approach, allowing medical staff to move to PILS’ facilities. This brought the service closer to the most vulnerable individuals.

You also coordinate a cooperation platform in the Middle East and North Africa region…

Dr. Lahoucine Ouarsas: Exactly—this is the MENA platform of Coalition PLUS. Given that our challenges are similar in culturally close countries, we have everything to gain by sharing our solutions. We have created a regional guide that outlines how to set up a differentiated service to deploy PrEP among key populations. Various training modules are available for doctors who prescribe PrEP, healthcare providers, field workers, and peer educators, and each association can adapt them to their local context.

Do you also conduct research projects together?

Dr. Lahoucine Ouarsas: Yes, because we face the same challenges—we collaborate and pool our efforts and expertise to reach hard-to-reach populations. How can we build representative samples of populations when there are obviously no lists of sex workers, transgender people, or partners of drug users? We have developed a protocol based on a sampling method tailored to hard-to-reach populations. Our method allows us to base our advocacy on solid data.

What are the key points of your advocacy with the authorities?

Dr. Lahoucine Ouarsas: First, we ask for the recognition of community expertise. We have proven that we are capable of prescribing PrEP and carefully monitoring patients, despite the complexity of managing the medications. We also advocate for the sustainability of funding, mobilizing domestic funding and seeking support from local elected officials. Lastly, we campaign for universal access to healthcare, dignity, and respect for rights—whether one has papers or not, regardless of one’s lifestyle.