Integrating Climate Change into Malaria Response in Sub-Saharan Africa

Despite continued investments and efforts by National Malaria Control Programs (NMCPs), the African continent is still struggling to curb the disease. The results fall short of expectations: malaria cases have only decreased by 11% since 2015, whereas the African Union had set a target of a 40% reduction by 2020. African countries are also facing a new global challenge that is reshaping the fight against malaria: climate change. By altering the geographical distribution and seasonality of the disease, it is forcing an urgent adaptation of prevention and control strategies. From December 2 to 6, 2024, the Initiative and the Institute of Applied Sciences Ruhengeri (INES-Ruhengeri) co-organized a training session in Musanze, Rwanda, focused on the impact of climate change on malaria. Representatives from 19 French-speaking sub-Saharan African countries gathered to discuss control strategies that take this new reality into account.

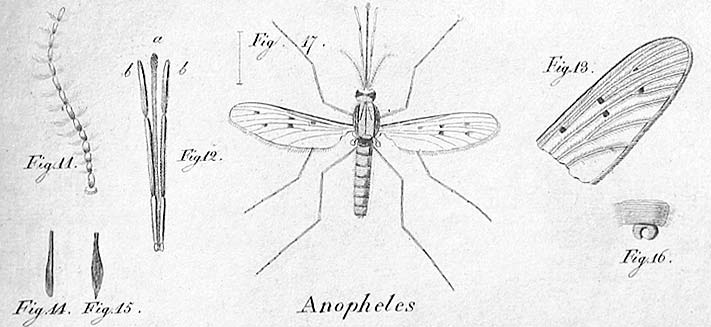

Historically referred to as the “marsh fever,” malaria is an ancient disease closely linked to wetlands, swamps, and riverine areas. In 2023, sub-Saharan Africa bore a disproportionate burden of the disease, accounting for 94% of global cases and 95% of malaria-related deaths. The region’s climatic conditions are highly conducive to the proliferation of female Anopheles mosquitoes, the vectors of the disease. Malaria is thus classified as a vector-borne pandemic: these mosquitoes, carrying the Plasmodium parasite, transmit it to human hosts through their bites.

“The symptoms of this disease are similar to those of the flu: fever, headaches, possible diarrhea, and joint pain,” explains André Tchouatieu, a physician with Medicines for Malaria Venture and a speaker at the training on the impact of climate change on malaria, held in Rwanda in December 2024. Without proper treatment, the infection can be fatal.

Sub-Saharan Africa faces significant challenges in its fight against malaria, including weak health systems, inadequate healthcare coverage, and a lack of public awareness. To make matters worse, mosquitoes and parasites are progressively developing resistance to existing treatments and insecticides. “Climate change makes the situation even more complex,” adds André Tchouatieu. “It’s a new variable that’s redefining the rules of the game.”

Training on Malaria and Climate Change in Rwanda

To address the challenges that climate change poses to malaria control, L’Initiative and INES-Ruhengeri brought together decision-makers from the NMCPs of 19 sub-Saharan African countries in Musanze, Rwanda. Over four days, participants attended multidisciplinary sessions covering epidemiological surveillance, innovative control methods, climate modeling, and forecasting. The goal was to provide tools and practices that will help countries prepare for the impact of climate change on malaria.

Participants shared their experiences, discussed challenges, and exchanged views on the effectiveness of initiatives implemented in their respective countries. A consensus emerged around key action priorities, notably the development of integrated surveillance systems that combine epidemiology, meteorology, and entomology.

Climate Change Is Redefining Malaria Transmission Dynamics

“Weather disruptions are reshaping transmission maps—they increase the risk of outbreaks in previously stable areas and reduce it in others. Floods and expanding droughts alter the conditions for mosquito development, requiring constant adaptation of control strategies,” explains André Tchouatieu.

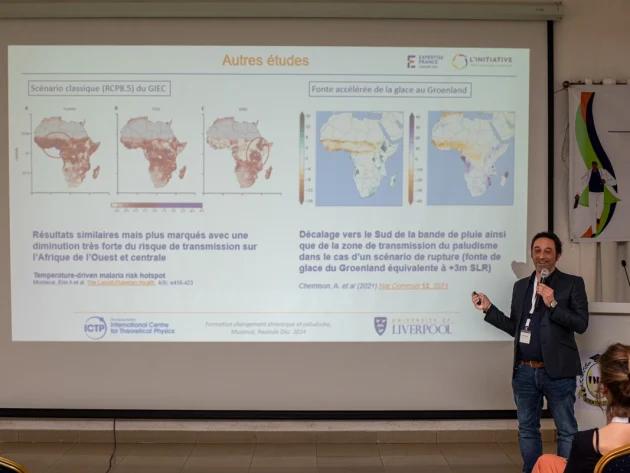

Closely tied to weather patterns, local biodiversity, and seasonal cycles, malaria is highly sensitive to climate change. Cyril Caminade, an expert in modeling vector-borne diseases in the context of global warming, confirms Tchouatieu’s observations in the second episode of the podcast series produced by L’Initiative for this training event. He highlights the complexity and non-linear nature of climate effects on malaria spread—changes in weather conditions can lead to disproportionate or unexpected outcomes.

Climate-related disasters present complex challenges. Heatwaves may have a positive effect on malaria control by reducing mosquito populations, which are sensitive to extreme heat. At the same time, they can cause population displacement, increasing contact between people from different regions—where malaria parasite strains and mosquito species may differ. These human movements complicate both disease control and patient management. Floods and other extreme weather events can also damage healthcare infrastructure, making access to treatment more difficult.

André Tchouatieu and the history of Malaria

Cyril Caminade on climate change and malaria

The Effects of Climate on Malaria Vector Mosquitoes and Their Environment

Malaria transmission occurs primarily during monsoon or humid, rainy periods. Rainfall creates breeding sites for Anopheles mosquitoes, which lay their eggs in clean, stagnant water. For instance, in Sahelian regions, the transmission period typically runs from July to October, with clinical cases—i.e., individuals infected with the disease—appearing one to two months after the rainy season.

Climate change is altering these environmental conditions—and, by extension, established malaria prevention and treatment strategies. “The consequences of climate change are already noticeable,” observes Cyril Caminade. “On the Katanga Plateau (Democratic Republic of Congo), the transmission season has already shifted by a month. In the western Sahelian band, exceptional monsoon seasons confirm the projections of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), with longer transmission periods and the emergence of newly affected districts.”

Temperature and rainfall variations affect not only the environment but also the biology of mosquitoes and the parasites they carry. “It’s important to understand that Anopheles mosquitoes have very specific biological traits. They are ectotherms, meaning they do not regulate their body temperature. This makes them particularly sensitive to climate variations. Temperature directly influences their biting frequency, reproductive cycle, and the speed at which the parasite develops inside the insect,” explains the Africa-focused climatologist.

According to Cyril Caminade, a race is underway between the speed of climate change and the adaptability of vectors and parasites. Anopheles mosquitoes have already shown their capacity to evolve by settling in urban areas—once considered unsuitable for their proliferation—and by shifting their biting schedules. “Despite significant uncertainty about the exact, concrete effects of climate change on malaria transmission dynamics, it is possible to make projections by combining climatology with epidemiology,” Caminade concludes.

Rwanda at the Forefront of the Climate Challenge

“It’s currently raining in Rwanda, even though the rainy season should have ended nearly two months ago,” notes Corinne Merle, a speaker at the training session and public health physician with TDR, the WHO’s Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases. The country is experiencing significant shifts in malaria transmission, particularly in high-altitude areas that have historically been less affected by the disease. In response to this new reality, Rwanda has positioned itself as a model of adaptation.

The Rwandan authorities have adopted a One Health strategy, which simultaneously addresses human, animal, and environmental health—including the climate dimension. Aware of the climate-related challenges, the National Malaria Control Program (NMCP) quickly implemented targeted measures, such as deploying sentinel sites for entomological and meteorological surveillance. In parallel, the Rwandan government has developed cross-sectoral climate policies to tackle climate change issues holistically. More recently, in 2024, it launched a Climate Desk aimed at coordinating research focused on the impact of climate change on the health sector.

The Role of Modeling in the Fight Against Malaria

Climate change is making malaria transmission pathways increasingly uncertain. Modeling—a decision-support tool based on mathematical principles—helps anticipate the impact of interventions on the evolution of the epidemic. This scientific method gained prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic. It enables policymakers to prioritize strategies and can also serve as an advocacy tool. “Models can answer specific questions, such as comparing the effectiveness of different types of mosquito nets or evaluating the outcomes of intervention strategies under certain climate change scenarios,” explains Émilie Pothin, an infectious disease modeler at Swiss TPH, who also took part in the training in Rwanda. These models also allow for precise mapping of local specificities: mosquito species, disease dynamics, climate conditions, and resistance patterns. By developing and testing different scenarios, researchers can assess the potential effectiveness of interventions and design context-specific prevention strategies.

However, integrating climate change into these scientific models is not straightforward. “Models must account for the mosquito’s full biological cycle, its interactions with the environment, and human dynamics,” the researcher emphasizes. Temperature, humidity, rainfall, and human behavior influence exposure to bites and access to healthcare—factors that must all be considered to refine predictions. To do this, scientists collect and analyze a wide range of data from studies, fieldwork, and health reports. This work, carried out in collaboration with local stakeholders, is essential for producing reliable, actionable models. The more accurate the data, the better these tools can identify high-risk areas and guide prevention strategies. In the context of climate change, modeling is proving to be a key lever for more effective malaria control.

Integrating Climate into Malaria Control Strategies

Malaria control programs must now be equipped with tools adapted to climate change. In this context, the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR), a WHO-hosted initiative, supports National Malaria Control Programs in optimizing their strategies. Corinne Merle, public health physician and epidemiologist with the TDR department, and guest trainer in Musanze, highlights three interdependent priorities: “To strengthen research and intervention capacities, robust surveillance systems must be established, particularly in areas where malaria was not historically present. At the same time, it is important to implement an early warning system that incorporates climate data to allow for rapid response. Lastly, optimal adaptation strategies must be developed.” An effective malaria control system is thus based on comprehensive surveillance (of vectors, the disease, climate, and resistance), an early warning mechanism, and evolving adaptation strategies.

The development of these strategies requires modeling and various types of research. Fundamental research explores complex questions: how does global warming affect mosquito resistance to insecticides? How do extreme weather events influence malaria transmission? Clinical research focuses on developing innovative solutions. New vaccines, drugs, mosquito nets, and vector control strategies are constantly being explored to keep up with the rapid evolution of the parasite and its vector. Operational research then takes over, aiming to optimize these tools in specific local contexts. The goal of eliminating malaria by 2030 in sub-Saharan Africa—and ultimately its global eradication—depends on scaling up research efforts and securing funding. Research makes it possible to develop new interventions, particularly to tackle the emerging challenges posed by the disease, such as resistance, while targeting the most at-risk areas. In this way, research saves thousands of lives.

Corinne Merle and the role of research

In the face of the environmental crisis, research remains a key pillar in the fight against malaria.

Dr. Corinne Merle, epidemiologist at the WHO, shares her insights on the importance of investing in innovative solutions tailored to emerging climate challenges.

An episode that highlights the connection between science, public health, and resilience in the face of epidemics.

Émilie Pothin and prioritization strategies

Modeling: a discreet yet powerful tool to anticipate and better target the fight against malaria.

Emilie Pothin, an expert at Swiss TPH and the Clinton Health Access Initiative, explains how this approach makes it possible to simulate the impact of interventions, integrate the effects of climate change, and guide political decisions.

A strategic, scientific—and advocacy—lever.

Toward a Multisectoral and Regional Approach in an Interconnected World

“What matters is to share information, as we did during this training, in order to inspire each other and identify best practices that can be replicated from one country to another,” said Corinne Merle in her podcast. The fight against malaria is now moving toward a collaborative, multisectoral, and adaptive approach in the face of climate-related challenges. The Musanze meeting concluded with several recommendations, including the need to strengthen cross-sectoral and academic collaboration, and to regularly share ideas and solutions at the pan-African level.

Climate variability fuels environmental degradation and leads to natural disasters, extreme weather events, heightened food and water insecurity, economic disruptions, and conflicts. Climate change is one of the major health challenges of the 21st century. “It is complex because it is multifactorial, so it requires equally complex responses and diverse expertise,” said Jane Deuve, Coordinator of Scientific Engagement and Knowledge Sharing at L’Initiative, during the opening of the training in Rwanda, addressing the representatives of the National Malaria Control Programs. The combined challenges of malaria control and climate change call for an integrated approach, mobilizing meteorological services, education, urban planning, agriculture, as well as local communities and NGOs. “More than a health challenge, climate change is a test of our ability to support one another and to collaborate,” concluded Jane Deuve, opening a new chapter in this collective fight.

Malaria: What Challenges Lie Ahead in the Face of Climate Change?

Listen to the podcast featuring Jane Deuve, André Tchouatieu, Cyril Caminade, Corinne Merle, and Émilie Pothin — key speakers who made a strong impact during the training on malaria and climate change in Rwanda. They dive deeper into the current situation and the challenges ahead.