Understanding Harm Reduction and Opioid Substitution Therapy

Public drug policies have long swung between repression and injunctions to undergo detoxification or adopt abstinence. Faced with the complex reality of substance use and the pandemics of HIV, viral hepatitis and tuberculosis, another logic has emerged, pragmatic and centred on preserving life and rights.

Harm reduction (HR), reinforced by opioid substitution therapy (OST), is not a mere technical recipe — it is the result of public-health choices aimed at saving lives. In Côte d’Ivoire, these approaches are being practised daily within the Ya-Fohi project, heir to work that began in 2015 and now run by Espace Confiance with the support of L’Initiative.

Origins and meaning of a life-saving strategy

Harm reduction was born around the turn of the 1980s, when the HIV epidemic confronted the world with an obvious fact: as long as drug use exists, its health and social consequences must be minimised without demanding immediate cessation. In this respect, OST replaces illicit opioids with a prescribed, medically supervised medication. In doing so, the strategy builds a bridge between places of consumption and healthcare — bringing back into the health fold people who had been excluded by marginalisation and stigma.

On the ground in Côte d’Ivoire, as Dr Zahoui Feriole, medical coordinator of the Addiction Care and Support Center (ACSC) in Abidjan, reminds us: “Harm reduction is a policy that aims to reduce the harms associated with drug use, such as HIV and tuberculosis infections, which are highly prevalent among people who use drugs (PWUD) in Côte d’Ivoire. This approach has been in place here since 2015 to reduce the infectious reservoir represented by this population.” In other words, it aims to reduce the epidemic’s collective burden by responding to people’s concrete needs.

Harm reduction: concrete tools, measurable effects

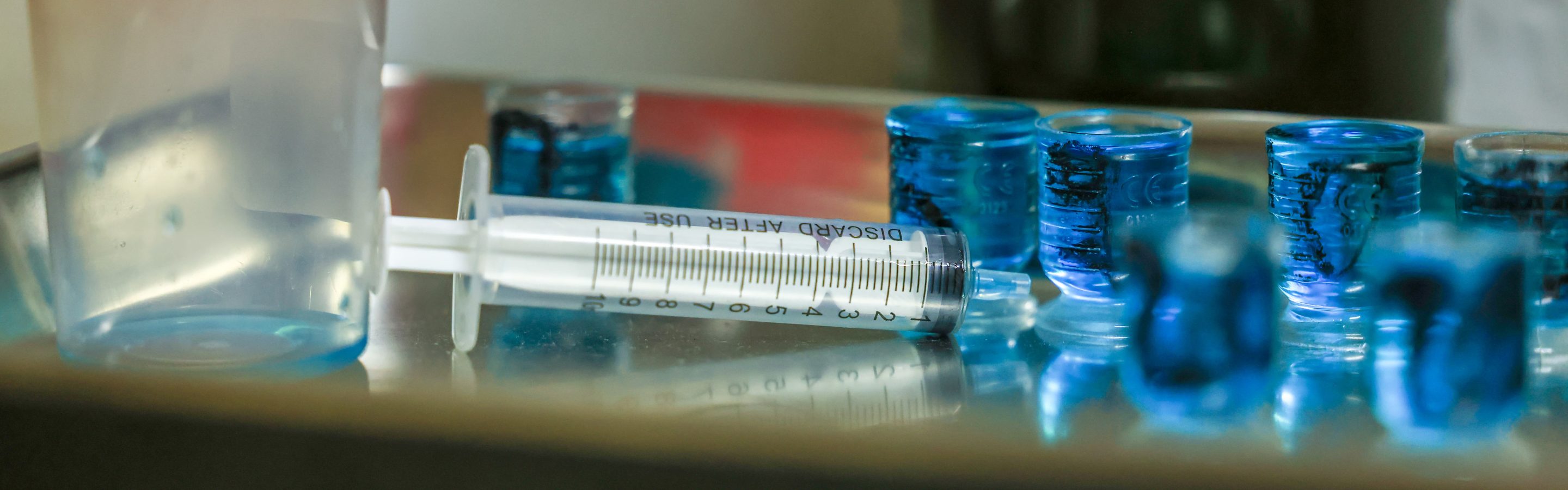

Harm reduction rejects abstraction. In the field, it translates into concrete measures: distribution and exchange of sterile injecting equipment, prevention kits, simplified access to testing and consultations, and above all the mobilisation of peer educators — former or current users trained to act as trusted intermediaries. These actions primarily aim to reduce blood-borne transmission of HIV and hepatitis C, break isolation and create pathways to care.

The impacts are tangible. For example, within the Ya-Fohi project supported by L’Initiative in Côte d’Ivoire, HIV prevalence among people who use drugs fell from 9.8% to 2% — a shift explained by regular testing, the provision of sterile equipment and the progressive building of trust. At a larger scale, international studies also show significant reductions in new infections among participants in needle-exchange programmes.

The objective of HR is clear: drive back disease by fighting marginalisation and opening the door to care.

OST as a reinforcement of HR: stabilise to treat and reintegrate

OST is part of the HR strategy. It substitutes illicit opioids with a prescribed medication (methadone or buprenorphine) that stabilises use, avoids the highs and lows typical of uncontrolled consumption and reduces risky practices. In other words, OST creates the medical and social conditions for a person to access care regularly, adhere to treatment and envisage a new start in life.

“Opioid substitution treatment is one of the pillars of harm reduction. In Côte d’Ivoire, that is methadone: it responds to the demand for help with withdrawal and stabilises beneficiaries’ lives,” explains Dr Zahoui Feriole.

In the Ya-Fohi project, methadone is dispensed daily to a monitored group; the stability thus regained often becomes the condition for reintegration: some beneficiaries return to work, rebuild family ties and gradually escape extreme precariousness. From a health perspective, OST reduces the risk of HIV and tuberculosis transmission by encouraging access to testing and treatment centres, and reduces overdose-related mortality.

Frédéric, a former PWUD, sums up this turning point: “OST gave me a new life. I can think about my health and my plans.”

Why target people who use drugs?

The logic is simple and powerful: targeting a group that concentrates a high incidence of infectious diseases can alter the circulation of pathogens across the whole population, while enabling the testing and treatment of every individual, including the most marginalised — yielding both individual and public-health benefits. PWUD accumulate vulnerability factors — precarious living conditions, lack of stable housing, malnutrition and social marginalisation — which increase their exposure to HIV, tuberculosis and hepatitis. Stigma and marginalisation act as powerful barriers to access to care; targeted interventions aim specifically to dismantle them.

By protecting those most exposed, we protect both those individuals and society as a whole.

Ya-Fohi: deploying the approach in Côte d’Ivoire

Since its launch, the project has implemented coordinated, concrete actions: at the ACSC in Abidjan, a fixed site offering holistic care combines testing, OST and psychosocial support. On daily outreach rounds, peer educators crisscross the ghettos to distribute kits, inform and refer people. For example, in San-Pédro, awareness sessions and rapid tests bring prevention closer to people’s everyday lives.

In Côte d’Ivoire, OST exists but remains very rare — an active cohort receives a daily dose of methadone together with medical and psychological follow-up. Nevertheless, the experience also reveals vulnerabilities: importation and supply procedures for methadone can cause stock outs, and geographic scaling of the programme requires further training for health staff, community workers and law-enforcement officers. Local ownership, driven by Espace Confiance and its partners (APROSAM, ASAPSU, ENDA Santé), is central to the strategy: it is what enables the model to be sustained and replicated elsewhere, but it still depends on the availability of inputs.

A public health and dignity strategy

Harm reduction is primarily a strategy of humanity: it protects life, restores dignity and opens the way to a fresh start. Its effectiveness — including that of OST — is documented, its health benefits measurable, and when implemented with communities it transforms the relationship between users and the health system. Ya-Fohi illustrates this logic: by combining pragmatic actions, committed peer educators and holistic support, it demonstrates that HIV, viral hepatitis and tuberculosis transmission can be reduced while restoring a place to those so often forgotten.

To see these approaches in action and extend this reading, watch the Ya-Fohi report: images that make tangible what words try to explain.