Tuberculosis in Rwanda: geospatial analysis to identify missing at-risk populations

While Rwanda treats 91% of its tuberculosis patients and with success for 89%, according to the WHO, some populations slip through the screening net and may infect others. With technical assistance from L’Initiative, the National Tuberculosis Control Program has developed a method to identify these key and vulnerable populations (KVP) through geospatial analysis. This approach defines, locates, and estimates populations at risk of diseases that may have been missed by the healthcare system. Epidemiologists Dr. Patrick Migambi and Ente Rood discuss this innovation in the fight against tuberculosis.

What is the tuberculosis situation in Rwanda?

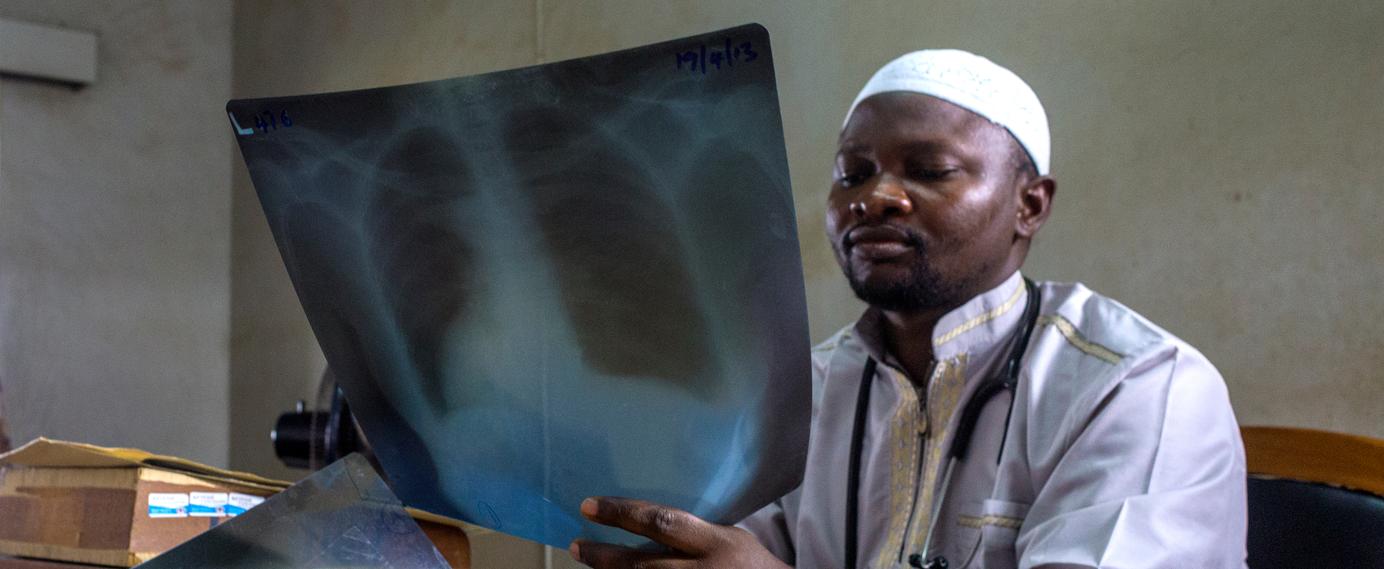

Patrick Migambi: By implementing some of the WHO’s recommendations, we have significantly improved our tuberculosis detection rate, increasing it from 69% to 91%. But we hope to go even further, particularly by curing at least 88% of affected individuals nationwide.

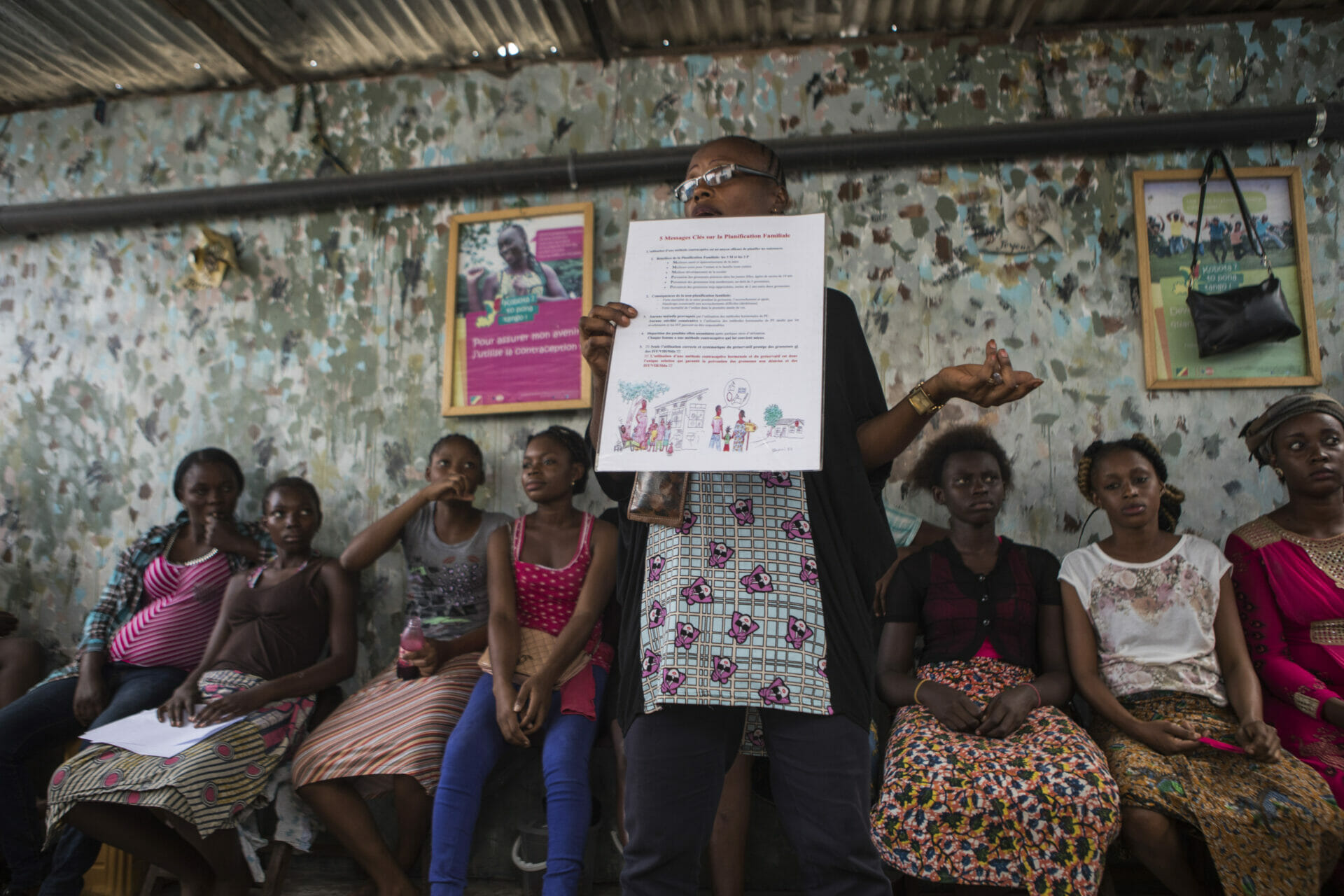

Ente Rood: The Rwandan tuberculosis program is indeed very effective, with a broad diagnostic network. However, there are still small groups of key and vulnerable populations (KVP), particularly marginalized groups, who are not identified by the health system and among whom the disease continues to spread.

Why is it difficult to identify these communities?

Ente Rood: These challenges are common and are neither specific to Rwanda nor to tuberculosis. For this epidemic, as well as many other infectious diseases, one of the biggest challenges lies in determining who are the people at risk, where they can be found and how many people with TB are missed. People commonly only seek medical care when they have symptoms, when they know they are sick, when they have access to healthcare, and when they can afford it. You can imagine there are many reasons why people are not aware of the possibility that they have TB, such as lack of money, lack of time, or not seeing the necessity to seek care when they have TB symptoms.

Rwanda has high-quality tuberculosis diagnostic tools. The main challenges, therefore, stem more from the social stigma associated with screening. The infrastructure is largely in place, yet people are still being missed by the system; the remaining barriers are primarily socio-economic.

Patrick Migambi: From an epidemiological perspective, it is crucial to target the people most at risk. The disease is not evenly distributed—for example, there are relatively few cases in the general population. This is why we rely on mapping and geospatial tools, allowing us to go into as much detail as possible, down to the smallest administrative unit, and estimate risk factors at every level.

To achieve this, as part of this technical assistance, the Mapping and Analysis for Tailored Disease Control and Health System Strengthening (MATCH) methodology combined with a tool for estimating the size of key and vulnerable populations are used. Can you tell us more?

Ente Rood: The combination of the MATCH methodology and the KVP size estimation tool enables the establishment of a geostatistical approach to identify cases where at-risk individuals may have been missed by the healthcare system.

Patrick Migambi: The three main components of the MATCH approach are simple: identifying tuberculosis risks, assessing access to healthcare services, and reporting all detected and treated cases. All of this aims to improve diagnosis, reduce transmission, and curb the pandemic.

What does the MATCH methodology specifically consist of?

Ente Rood: We compare tuberculosis detection statistics with performance indicators. By considering the population’s socio-economic data, the spatial analysis of these results reveals anomalies in certain areas, which—once verified—can indicate the presence of vulnerable populations that have been missed by the healthcare system.

That data seems accurate, so why pair it with a tool for estimating the size of key populations?

Ente Rood: This KVP tool adds a more qualitative dimension. We interviewed representatives from various stakeholder groups to help us prioritize KVPs amongst 22 vulnerable groups identified in Rwanda. Together with the national tuberculosis control program and KIT, these representatives identified six KVPs which currently are not prioritized by the TB program, including sex workers, people who use drugs, migrants, people with alcohol use disorders, and others. We then worked to classify and estimate the size of these groups nationwide and to determine where increased tuberculosis testing efforts should be focused.

Patrick Migambi: Knowing the size of high-risk groups is essential for screening planning. It allows us to conduct a cascade analysis of the patient—not considering their case in isolation but within the context of their community. This information helps us design interventions and prioritize areas for action. During the intervention phase, we aim to identify people who are not yet in contact with the healthcare system. Do they recognize the symptoms of the disease? Do they know where to seek treatment? Are diagnostic tools available in their area? Finally, we check whether diagnosed individuals have received and followed their treatment, and confirm that they have fully recovered.

What was L’Initiative’s contribution to this project?

Patrick Migambi: This spatial and mapping analysis was recommended to us by the Global Fund. Since we were not familiar with this type of approach, we investigated other countries that had carried out similar work with the support of L’Initiative. We then requested technical assistance, which led to the collaboration between RBC and KIT.

Ente Rood: L’Initiative supported RBC’s project, and KIT was selected to lead this work. It also helped us gain access to certain public health data to feed the MATCH statistical models. Our collaboration has been very successful.