Ukraine: maintaining HIV care in a time of war

Funded by L’Initiative and implemented by the community-based organization 100% Life, the Fight for Life project supports a network of Ukrainian clinics that continue to provide HIV care despite the war. Dmytro Sherembey, a central figure of civil society and head of the coordination council of 100% Life, explains how maintaining treatment continuity has become a daily act of resistance in a country where more than seven million people have been displaced since 2022.

Keeping HIV care afloat during wartime

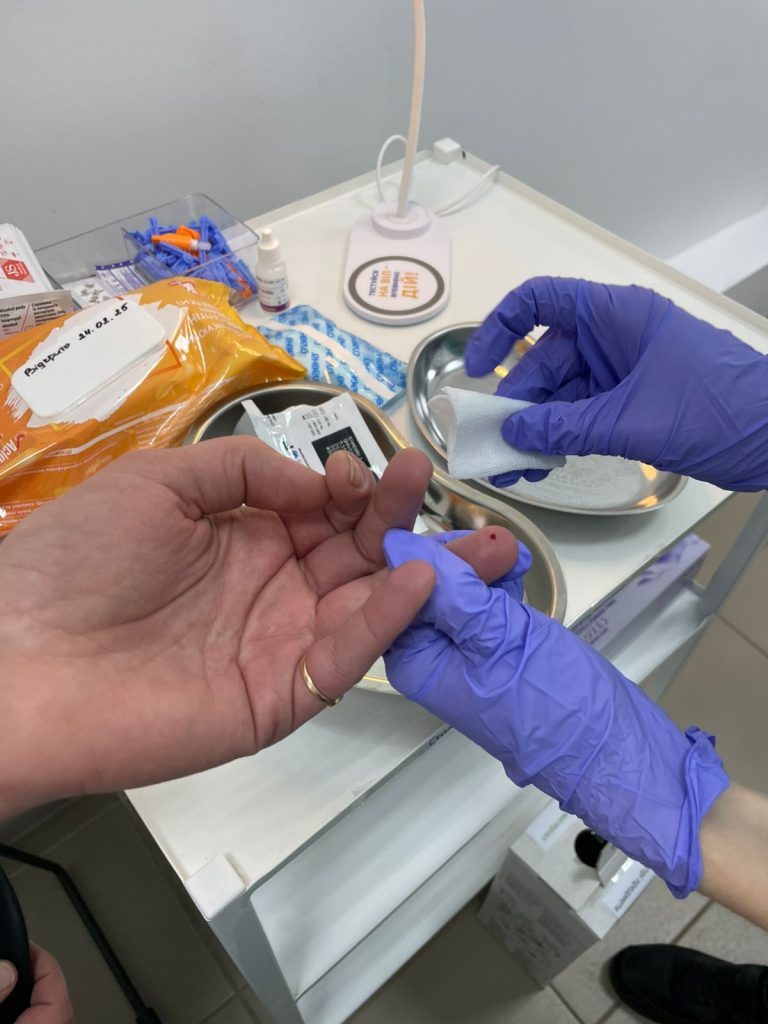

In Kyiv, Poltava, Rivne and Chernihiv, the community clinics of 100% Life continue to receive people living with HIV, users of PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis, a preventive treatment), patients on opioid substitution therapy, and a growing number of internally displaced people. Consultations follow one another despite air-raid alerts, power cuts, and an instability that has become structural since February 2022.

Dmytro Sherembey sums up the scale of the initial shock: “In the first months of the war, more than thirty facilities providing HIV services were destroyed or ceased operations.” The impact was immediate: “The most significant effects were the destruction of infrastructure, the disruption of logistics, and large-scale internal displacement.”

In 2022, HIV testing volumes fell by 23%, late diagnoses increased, and more than seven million people were displaced within the country. Public health services, weakened by shelling and by the mobilisation of part of the health workforce, were forced to scale down their activities. In this context, community clinics became essential anchor points, ensuring continuity of antiretroviral treatment, medical consultations, and psychosocial support.

Over the months, 100% Life’s role in the response has become clearer: a national role in PrEP delivery through an integrated, dual-supervision model, and the continuation in Poltava of one of the few opioid substitution therapy programmes still fully compliant, within a complete clinical setup.

The organisation has continued to operate thanks to a solid clinical structure, tested well before the war. “Our approach relies on the high qualifications of our staff and on a well-organised multidisciplinary model”, Sherembey notes. Infectious-disease specialists, addictologists, general practitioners, psychologists and social workers work in a coordinated manner, a configuration that has proved more resilient than many public facilities. “Our extensive experience in remote service delivery also enables the team to work without interruption.”

This architecture made it possible to hold on as the system was faltering. In the clinics supported by Fight for Life, it translated into the continued delivery of essential services – medical consultations, antiretroviral treatment, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and opioid substitution therapy – sometimes replacing damaged public facilities. Nationally, HIV testing rebounded (+39.6%) following the initial shock, and access to first-line treatment, used by 120,000 people, was secured.

Rebuilding supply chains under fire

In the first weeks of the invasion, the supply chain collapsed: “the logistics of medicines and diagnostic supplies essentially came to a halt”, Sherembey explains. International suppliers stopped their deliveries; male drivers, eligible for mobilisation, could no longer leave the country. Inflation at times doubled or tripled the prices charged by local suppliers. The closure of the national warehouse in Boryspil forced an emergency relocation to Lviv.

An emergency corridor was then re-established: storage in Poland, special border procedures, and shipment onwards by Ukrainian Railways to Lviv. The U.S. government stepped in to secure the production and procurement of first-line treatment, essential for almost all patients.

Some areas remained inaccessible. “The connection between the Kyiv region and Chernihiv was blocked”, Sherembey recalls. Volunteers found a boat to cross a river and deliver treatment under fire. “One of our volunteer groups was killed: their vehicle carrying medicines and humanitarian aid was deliberately destroyed.”

As some routes gradually reopened, teams adapted their practices. “Ensuring continuity of antiretroviral treatment during wartime is a critical priority for our clinic”, Sherembey stresses. Strengthened teleconsultations, multi-month dispensing, postal delivery, individualised logistics — including to foreign countries or active combat zones: “a well-coordinated, individualised logistics system to deliver ART across Ukraine and abroad, including to military personnel on the front lines.” More than 1,000 internally displaced people were able to maintain their treatment through these emergency mechanisms.

Tracing patients scattered by the conflict

The destruction of the Mariupol HIV center left thousands of people without follow-up care. “The Mariupol HIV center was completely destroyed”, Sherembey notes. With no records or reliable patient lists, the team integrated into 100% Life began tracing patients one by one, across a population that had been widely dispersed. Around 1,800 people were redirected to other clinics; 500 are currently followed by the network. Nearly 3,000 remain unaccounted for.

Across the country, access to care had to be reorganised under emergency conditions: procedures were drastically simplified — “a patient simply needs to request help to receive the full range of services.” This flexibility also applies to people who fled abroad, often without their medical documents.

Military mobilisation has also created a major blind spot in the response. “Men, focused on protection and survival, stop paying adequate attention to their own health”, Sherembey explains. Many interrupt ART, abandon PrEP, or avoid testing for fear of the medical commission. Some return in severe clinical condition. Increased exposure to blood in combat zones heightens the risk of transmission at a time when prevention capacity is already under strain.

A response under pressure, an uncertain future

This pressure also weighs on the teams, who work under constant strain. “The clinic has recorded a significant rise in cases of professional burnout and post-traumatic stress among staff”, Sherembey observes. Patients themselves present more acute stress reactions, which adds to the psychological burden. Mobilisation and the exodus of part of the health workforce further weaken the response: “The medical system is extremely fragile due to large-scale emigration of personnel and mobilisation.”

At the same time, HIV prevention suffers from chronic underfunding, and key populations receive less attention. These dynamics, typical in wartime, increase the risks of transmission. “The main concern for the coming years is the expected sharp increase in new HIV cases”, particularly among military personnel and displaced people. Treatment interruptions, extreme mobility, and pressure on services create fertile ground for an epidemic rebound.

In this context, continuity of care relies on targeted support. Backing from L’Initiative has helped stabilise teams (salaries, burnout prevention), finance critical relocations, strengthen internal and international logistics, and maintain services for more than a thousand internally displaced people. A discreet but decisive contribution to preventing the collapse of the continuum.

Beyond this support, continuity of care remains the main barrier against a resurgence of the epidemic. The adaptations developed in Ukraine — individualised logistics, remote follow-up, simplified procedures — offer useful insights for other crisis settings. Sherembey sums up the spirit of this mobilisation: “We endure because we refuse to abandon our patients. That is, ultimately, the meaning of our work: to fight for life.”