Community preventive strategies to combat malaria

In Burkina Faso, malaria remains a major public health problem, with 11 million cases reported each year. To combat the disease, the WHO has recommended a proven strategy for the past 10 years: seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC). This involves using antimalarial drugs to prevent severe cases in children under 5 years old, who are highly vulnerable to the disease. These drugs are administered during periods of high transmission, in areas where the infectious burden is highest.

Although SMC has reduced malaria incidence in Burkina Faso, the disease continues to claim 4,000 lives annually, mostly young children. According to Paul Sondo, a researcher at the Health Sciences Research Institute (IRSS), this may be due to external factors. He leads the SMC-RST project on SMC, supported by L’Initiative, conducting operational research to make the implementation of this prevention strategy more effective.

In which health context does your study fit?

SMC takes place during the malaria transmission period. An antimalarial dose is administered twice to children, one month apart. The country’s political and health authorities are working towards widespread coverage of SMC, and the treatment acceptance by the population is good. However, observations suggest that the national prevention strategy could be more efficient. Therefore, this study was conducted in the Nanoro health district, in the western region of Burkina, where the malaria season lasts from June to October, with a transmission peak usually in the last month.

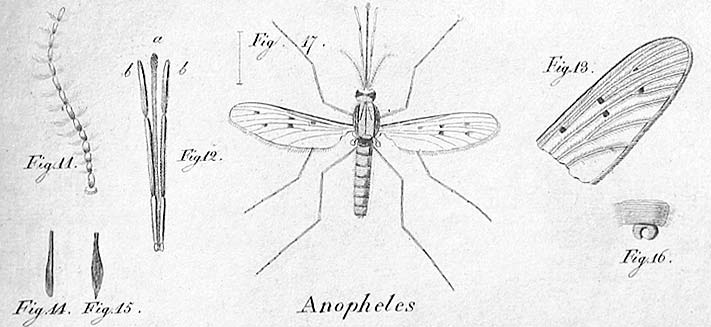

The initial hypothesis was that children, despite receiving SMC treatment, would continue to be infected within their family households: the proximity to individuals who host malaria parasites without developing the disease may be the cause. These asymptomatic carriers are neither detected nor treated. Under these conditions, the disease transmission cycle would not be interrupted, and children would not benefit from the expected effects of SMC.

In which health context does your study fit?

We combined preventive strategies to strengthen the impact of SMC and sustainably reduce malaria incidence. Between 2021 and 2022, we conducted a randomized controlled trial.

526 households, where children aged 3 months to 5 years live, were selected and randomly assigned to two groups. In the first group, SMC was implemented as per standard practice. In the second group, it was coupled with screenings and treatments for other household members. In both groups, children were followed with monthly home visits during high transmission periods. Parents also had to visit health centers if any household member fell ill.

What were the results of your study?

Our hypothesis was confirmed. We observed a correlation between the number of children testing positive for the disease and the number of infected individuals in their surroundings. In the group where SMC was combined with the additional preventive strategy, the cumulative incidence of malaria was significantly lower than in the first group. This intervention appears to limit the transmission cycle within the household and strengthen the effectiveness of SMC in children under 5 years old.

What is the role of the community interventions in the fight against malaria?

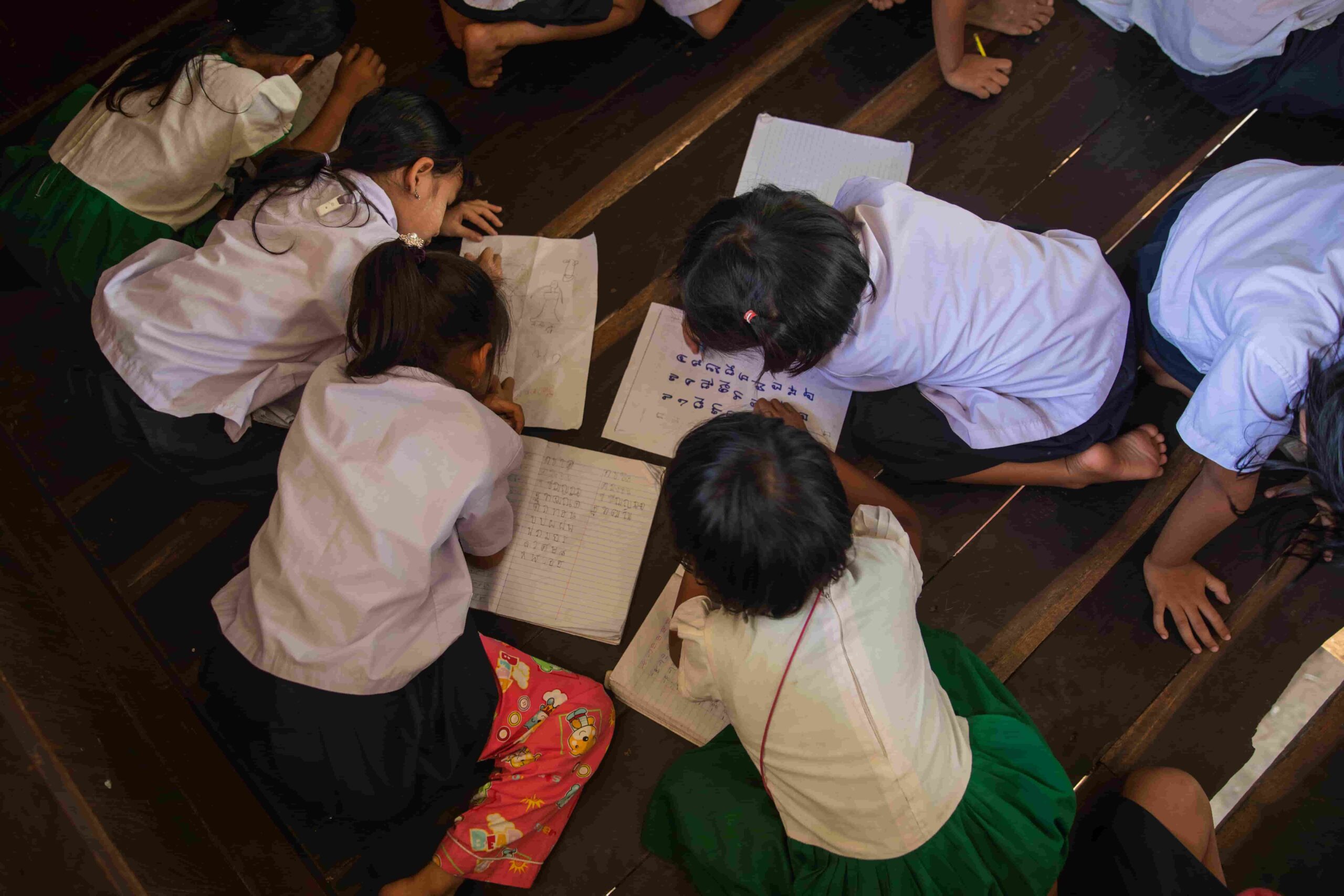

Community interventions are fully integrated into the SMC strategy and into our project. Thanks to these interventions, the population has become increasingly engaged in the process as the study progresses.

In our project, community involvement is manifested through door-to-door campaigns to raise awareness about malaria. It’s essential for the population to better understand the disease’s transmission mechanisms and the strategies developed to combat it. This health education significantly increases knowledge levels about the disease. We have evaluated it qualitatively through individual interviews and group discussions. These community interventions also help build trust in healthcare personnel. As a result, residents are more involved, more inclined to undergo screening and treatment for example, and more likely to use mosquito nets in their homes.

What is the role of the community interventions in the fight against malaria?

Climate change, for instance, can alter rainfall patterns, affecting mosquito proliferation, the disease’s vector. A strategy like SMC, which targets transmission peaks, must adapt to ensure interventions begin at the most opportune time. In the Nanoro district, we’ve observed that the peak transmission period is shifting later in the year. If it typically occurs in October, it sometimes extends into November or even December.

What are the next steps following the attainment of the study’s results?

As for the next steps after obtaining study results, we are currently disseminating the findings. We will also share them with Burkinabe policymakers and the international scientific community.

On the research front, one avenue we continue to explore is the consequence of this combined preventive strategy on parasite resistance. Implementing it on a larger scale and over a longer period could exert drug pressure and potentially lead to parasite resistance, risking a decrease in intervention effectiveness.