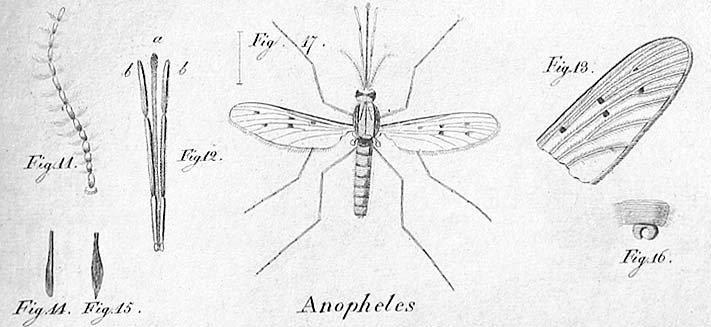

Anopheles stephensi is gaining ground in Africa. This insect species, native to South Asia and the Arabian Peninsula, carries the two most deadly strains of the plasmodium parasites—falciparum and vivax—that cause malaria. It appeared in the Horn of Africa in 2012, in Djibouti, a country that had almost eliminated the disease, with only 27 recorded cases per year (compared with 73,000 in 2020). Anopheles stephensi has since also been detected in Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia, and, more recently, in Nigeria and Kenya.

Urban areas now also at risk from malaria

Anopheles stephensi shows an alarming resistance to most insecticides, such as DDT and pyrethroids. The invasive species could undermine efforts to control and eliminate malaria in Africa. For the World Health Organization (WHO), the mosquito’s spread is “a major potential threat to malaria control in Africa,” where the disease burden is already particularly high, with 400,000 people dying from malaria in Africa every year.

According to a study by the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, the species could endanger 126 million people in Africa if it spreads to the continent’s major cities—a scenario specialists are particularly concerned about. Unlike other mosquitoes that mainly thrive near lakes and swamps, such as Anopheles gambiae, Africa’s most prevalent species, Anopheles stephensi can tolerate pollution and is highly adaptable to different climatic and environmental conditions. It can, therefore, survive in previously unaffected places, like cities, where it thrives in stagnant water, such as in storage containers. This allows it to breed all year round and remain active in the dry season.

Its behavior is also distinctive. While other African Anopheles bite humans at night and usually indoors, stephensi bites at dusk when the air is still warm and does so outside, limiting the effectiveness of insecticidal nets. Other tools, such as indoor residual spraying, may not work to contain this species.

A mosquito species still under study

Responding to this challenge will be tough, with many studies on the mosquito still underway. The aim is to gain a better understanding of the new species and to explore the best ways of monitoring its behavior and controlling its spread in already-infested areas. “It must be emphasized that we still don’t know how far this species of mosquito has spread or what problem it poses or could pose,” says Dr. Jan Kolaczinski, who heads the Vector Control and Insecticide Resistance Unit of the WHO’s Global Malaria Programme. While its presence correlates strongly with the sharp increase in malaria cases, initial evidence confirms this causal link1 and sheds light on the extent to which Stephensi could cause outbreaks of malaria in other cities.

A 2020 model taking into account various parameters (temperature, rainfall, etc.) suggests it could become established in 44 African cities with more than one million inhabitants, such as Bamako, Dakar, or Cairo. The WHO is coordinating several initiatives in response to this risk.

Promising courses of action for Africa

One such initiative, launched by the WHO in 2022 and updated in 2023, aims to support an effective regional response across the African continent. It is based on five pillars: increased collaboration between countries’ healthcare systems; stronger surveillance to determine the extent of the spread of Anopheles stephensi; improved information-sharing on the mosquito’s presence; the development of guidance for national malaria control programs; and prioritization of research to assess the impact of existing operations and tools. Lessons drawn from dealing with Anopheles stephensi in India, where the mosquito has caused malaria outbreaks in urban areas, could also be useful. For example, introducing strict regulations on water storage has proven effective in curbing the spread of the disease.

The two malaria vaccines now approved by the WHO, RTS,S in 2021 and R21 in 2023, bring hope. They both act in a similar way which works by creating antibodies against Plasmodium falciparum, the deadliest form of malaria parasites and allows the reduction of severe cases by 30%. The demand for malaria vaccines is significant, with 20 African countries planning to introduce malaria vaccines into their programs in 2024.

Notes et références

- Emiru, T. et al Nat Med 29, 3203–3211, 2023

For more information: “Over 1 million African children protected by first malaria vaccine” article by WHO.