Tuberculosis: building community capacity

A strategic initiative led by the Global Fund in five countries in West and Central Africa seeks to support community actors and build their capacities. Nuccia Saleri is working for greater devolution of responsibility to communities in countries that face the challenges of remoteness and insecurity.

Can you describe the Global Fund’s strategic initiative?

During the last replenishment cycle, Burkina Faso, Chad, Congo, Mali, and Niger received catalytic funding from the Global Fund for innovative work and pilot projects to detect missing cases of tuberculosis and improve access to treatment. In 2021, further funding was made available for technical assistance. As a result, countries have requested technical support to implement their initiatives using these catalytic funds.

My mission for the Global Fund is to support the implementation of these catalytic funds and new grants. In order to assist countries, we have set up working groups bringing together civil society actors, national tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS programs, partners such as Expertise France and the WHO, as well as laboratories and other national institutions financed to implement tuberculosis interventions. These are aimed at assessing the main activities and identifying and overcoming any difficulties encountered.

Why is devolution to the communities a challenge?

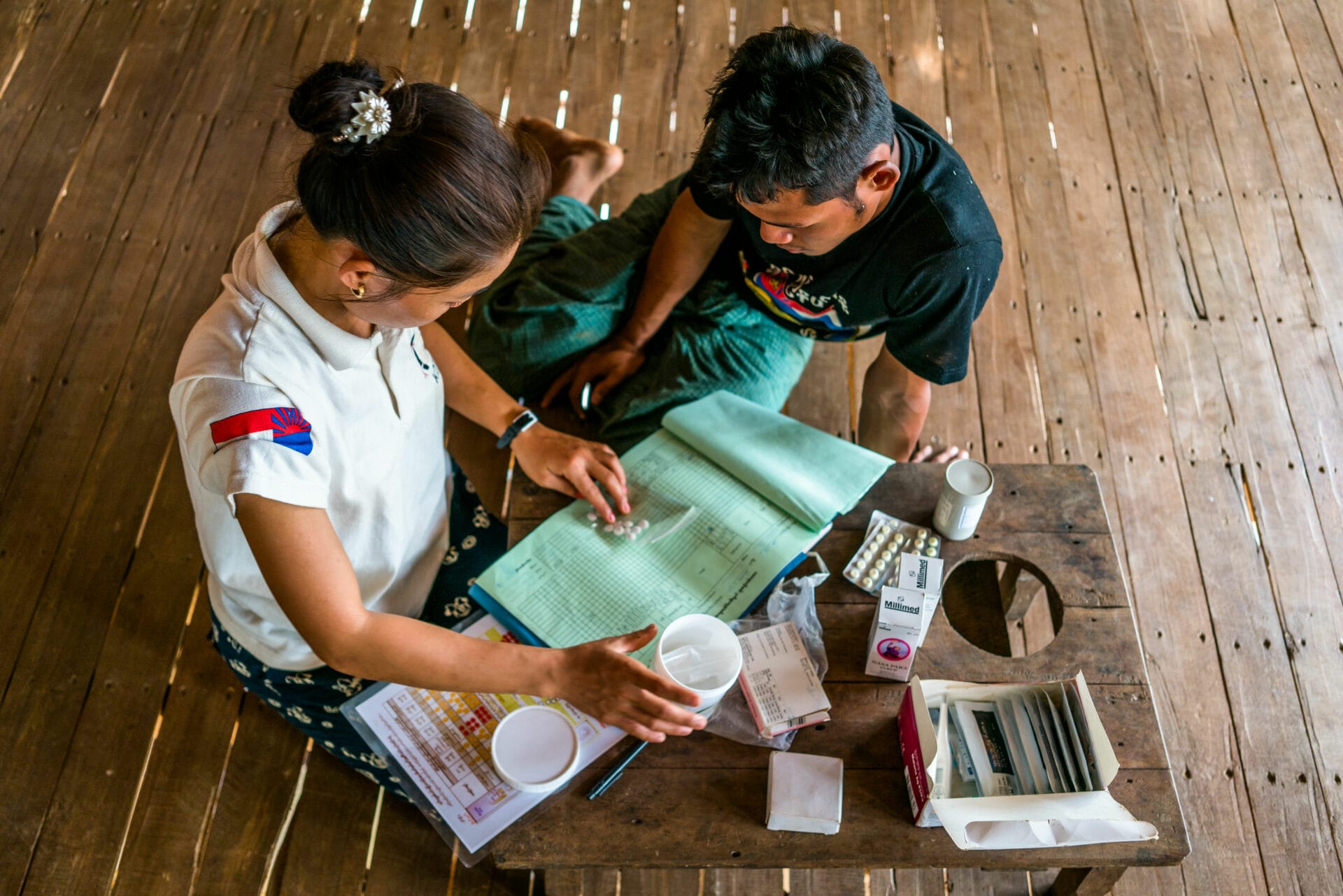

The security challenges in West and Central Africa are manifold. People have difficulty accessing health facilities where they have not closed down. To date, only Burkina Faso has developed a contingency plan to address the situation. Developed using technical and financial support from the Global Fund’s strategic initiative, the plan includes strengthening the role of humanitarian NGOs and community actors, for example, in transporting medicines to areas where health centers have shut down. It also aims to increase incentives for community health workers to continue working in these areas to treat and monitor isolated patients. Discussions are underway in Niger to develop a similar plan.

Generally speaking, the wariness of national programs toward civil society organizations is waning. Civil society organizations play a crucial role in reaching key communities, even in the remotest areas. They raise awareness of good hygiene practices, identify contact cases, and fight stigma against the sick. Unfortunately, Global Fund financing is still too low to implement a large-scale policy focusing on community actors.

Transporting samples is crucial in order to diagnose people who are screened. How does transport work in such conditions?

In Burkina Faso, the Ministry of Health has an agreement with the postal services to provide transport to secure areas. All samples are identified and registered, enabling results to be reported quickly and efficiently. This provides an example for other countries to follow. Capacity-building at the community level also needs to be explored so that civil society actors are involved in the collection and transport of samples to the laboratory closest to patients’ homes.

What specific support is provided in Niger?

Niger is a special case among the five countries concerned. The Global Fund requested my support in developing an active detection strategy for tuberculosis patients modeled on the approach taken in Burkina Faso. These countries have developed a “quality-based approach” to strengthen the capacity of health facilities to provide high-quality care and to detect missing cases of tuberculosis. This approach is currently being rolled out in four regions of Niger, targeting at-risk groups on a mass scale using mobile X-ray screening. However, the country’s security situation requires us to be cautious: in sensitive regions, we rely on NGO-trained peer educators to carry out this mass screening.

What about childhood tuberculosis?

More awareness-raising and training are needed primarily, especially at the community level. Children are particularly vulnerable within their families. This is where action needs to be taken as a matter of priority to improve the quality and uptake of therapeutic and preventive services. So far, this issue has not been sufficiently addressed, even by the national programs.

As for diagnosis, alternative methods have emerged, such as digital X-rays or stool sample analysis, although the latter protocol has not yet been approved by the WHO for children under 15 years of age.