RAITRA: challenges, results and prospects for an inclusive fight against tuberculosis

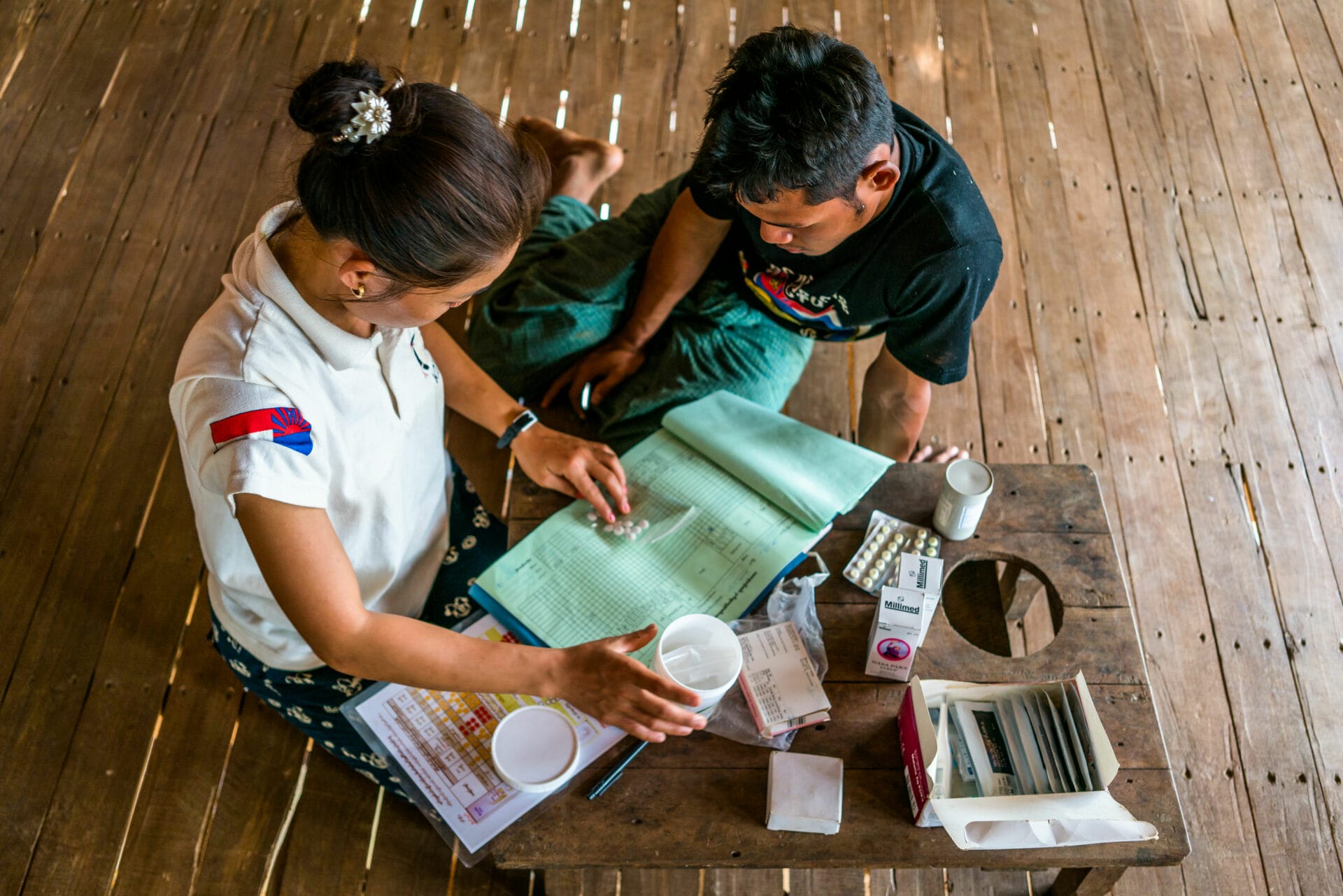

RAITRA is reinventing the tuberculosis response in Madagascar by placing psychosocial support and community inclusion at the heart of the programme. Implemented through a partnership between ATIA and three local non-governmental organisations (KOLOAINA, VAHATRA, MAMPITA) and supported by L’Initiative, the project links care pathways to field realities, strengthens coordination among stakeholders and consolidates local support — a genuine driver of treatment adherence.

In this joint interview, Fanja Anselme RANAIVO and Thierry Martin COMOLET reflect on the challenges they have met, the results achieved and RAITRA’s ambitions for scale-up.

How would you describe the RAITRA project?

Fanja Anselme RANAIVO: RAITRA is an innovative project supported by L’Initiative that acts upstream and downstream of biomedical care, weaving a relationship of listening and support between health professionals and vulnerable urban communities.

Thierry Martin COMOLET: Tuberculosis is above all a disease of social injustice. Our aim was to make screening and follow-up more effective — not simply by delivering medicines, but by accompanying patients day after day and by empowering local non-governmental organisations.

What major challenges have you encountered?

Fanja Anselme RANAIVO: RAITRA beneficiaries are often isolated, marginalised and deprived when faced with the geographic and economic barriers of public services. Free treatment alone is not enough: they fear stigmatisation at clinic reception after having had to pay to get there or walk long distances — sometimes across precarious bridges — to consult or collect their medicines. They frequently need local accompaniment to get through these steps. Such barriers can help explain, at the national level, a lost-to-follow-up rate of 8.5% among diagnosed and notified tuberculosis patients.

Thierry Martin COMOLET: Coordination with health services initially encountered some reluctance: some professionals perceived these new social actors as liable to blur established roles. Clarifying these misunderstandings required in-depth dialogue at all levels — central, regional and local.

What solutions have you implemented?

Fanja Anselme RANAIVO: We organised coordination meetings and shared our data with full transparency. KOLOAINA, through its openness to dialogue, was gradually able to lift resistance and establish clear collaboration protocols.

Thierry Martin COMOLET: The key tool was the visit report and monitoring indicators. By demonstrating our complementarity and the positive impact on adherence and support, we convinced stakeholders and proved the usefulness of the approach.

What concrete results does RAITRA deliver?

Thierry Martin COMOLET: An evaluation of the project’s first phase was conducted and the data speak for themselves: the project has supported nearly 2,000 patients receiving home-based follow-up, with an exceptional adherence rate of 98% without any financial incentives — a rare outcome for a six-month treatment regimen. Our surveys also show a positive increase in knowledge, although these data are self-reported.

Fanja Anselme RANAIVO : Beyond the numbers, what stands out most is the restored trust. Participants in support-group workshops often express relief at being able to speak without judgment, a sense of being heard and a better understanding of their care pathway. These spaces, among peers or with a trusted third party, help break isolation and strengthen adherence to treatment.

Has RAITRA strengthened capacities?

Fanja Anselme RANAIVO: Community workers have been trained in active listening, motivational interviewing and in recognising and addressing gender-based violence. The three partner CSOs, whose primary objectives were initially social, have even incorporated “health” objectives into their multi-year plans, demonstrating solid ownership of the gains.

Thierry Martin COMOLET: Our partners have thus shown that well-organised community interventions, based on social support, can be beneficial not only for tuberculosis and HIV but also for nutrition, family planning, management of chronic diseases and vaccination campaigns. Patients are lost to follow-up everywhere in the health system, and NGOs like ours help bridge the gap between health centres and individuals.

Is scale-up envisaged?

Thierry Martin COMOLET: Transmission of tuberculosis remains too high and malnutrition still contributes. By implementing a Phase 2 of this project, supported by L’Initiative, we aim to extend the programme geographically, integrate HIV, malaria and gender issues more fully, and strengthen technical training for tuberculosis staff in health centres.

Fanja Anselme RANAIVO: We want to capitalise on our psychosocial support expertise and propose a model that can be scaled up to health centres so that every patient has access to this protective safety net, wherever they live. Supporting community inclusion, recognising the contribution of civil-society organisations and making this type of accompaniment sustainable means giving everyone a real chance to recover by restoring trust in health services.