In the Greater Mekong sub-region, countries face significant public health challenges: addressing the growing burden of noncommunicable diseases while striving to eradicate pandemics. International aid is crucial for realizing these goals.

On June 10th and 11th, L’Initiative is hosting regional meetings in Bangkok to engage partners in discussions concerning issues regarding pandemics, in Southeast Asia, and to foster synergies among key stakeholders in the region.

During this event, Patrice Piola will discuss the health issues facing the Greater Mekong sub-region, an area he is well acquainted with. This zone comprises Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam—countries with diverse historical backgrounds and contemporary contexts. Today, they collectively confront a shared “dual burden” of public health challenges, encompassing diseases typical of both developed and developing nations.

With 25 years of experience, including roles at Médecins Sans Frontières and the Institut Pasteur, this epidemiologist specializes in program management and operational research in healthcare. He recently oversaw a malaria research program in Cambodia’s forested regions, backed by support from L’Initiative.

Patrice Piola

Medical epidemiologist with 25 years of experience (notably at Médecins sans frontières and L’Institut Pasteur) in medical program management and operational research.

What are the shared public health concerns among the Greater Mekong countries?

From a public health perspective, these countries are now classified as middle-income, with a population that’s more urbanized than in the past. The leading causes of death are noncommunicable diseases like cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular issues, affecting almost 60% of the population — a rate similar to that of more developed nations. However, typical developing country issues persist, including challenges in accessing healthcare, particularly in rural regions, as well as ongoing concerns about maternal and child health, and infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, malaria and HIV/AIDS. These nations grapple with a “dual burden” of public health, tackling both types of illnesses — occasionally worsening each other, such as diabetes and tuberculosis. Adding to this is a third significant challenge: pandemic readiness.

What crucial role do these countries play in preparing for pandemics?

The Greater Mekong region harbors vast biodiversity, but this wealth is threatened by climate change and urbanization. This creates favorable conditions for diseases like avian flu and COVID-19, as well as Zika, chikungunya, and dengue viruses. Thailand has a highly efficient diagnostic and laboratory network, placing it at the forefront of detecting emerging diseases. Nonetheless, international aid remains essential to support Thailand and assist other countries in the region in advancing.

Given that noncommunicable diseases are now the leading cause of mortality, is it necessary to prioritize infectious diseases like malaria, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis?

We are witnessing the results of tremendous efforts in recent years. For instance, malaria now claims the lives of only few people annually in the Greater Mekong region. However, the region has experienced the emergence of resistance to nearly all antimalarial drugs, including chloroquine and fansidar in the 1950s-1970s, and more recently to artemisinin. The spread of this resistance could have devastating consequences in countries with higher malaria prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa. Thus, there is a global commitment to “finish the job” and completely eradicate malaria in the Greater Mekong region, marking the culmination of immense efforts undertaken.

What is the path to achieve this goal?

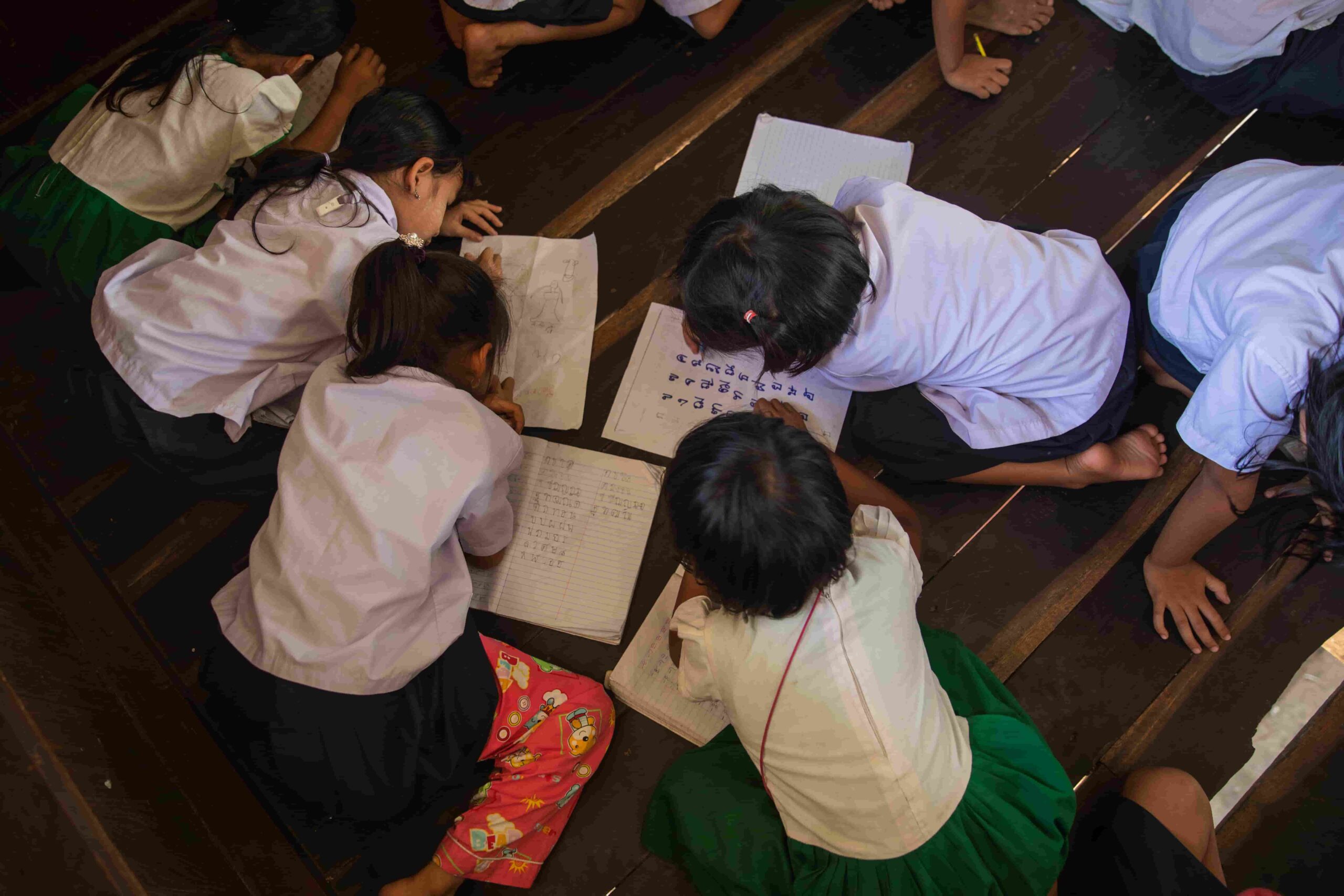

As a general rule, efforts should prioritize reaching out to the most vulnerable populations. In the case of malaria, this applies to those residing near forested areas. An exceptionally sensitive surveillance system is necessary to promptly address the initial reported case: identifying the village and ensuring comprehensive testing and treatment for all residents, if necessary, to prevent the transmission of malaria. Failure to do so risks the resurgence of the disease in the region, despite its current decline.

When it comes to tuberculosis, the most vulnerable populations encompass the poorest, the children, the elderly, the prisoners, the migrants, and individuals living with HIV/AIDS. Screening should be implemented within these groups to ensure treatment for every case.

Setting up an effective surveillance and combat system is feasible, but it rests on a network of physicians, caregivers, and nearby laboratories, closely serving the population. Skilled doctors are essential for recognizing the clinical signs of each disease, laboratories are indispensable for conducting tests, and information systems are crucial for transmitting data to national and international levels.

What steps can be taken to improve healthcare infrastructure in the Greater Mekong?

The requirements are comparable, yet each nation is at a distinct stage. Presently, Thailand boasts a high-quality healthcare system. Meanwhile, Vietnam, undergoing rapid economic growth, is enhancing its healthcare infrastructure, especially in rural regions. Cambodia and Laos are making progress but still require support to strengthen their hospital and healthcare center networks. Myanmar, on the other hand, faces deteriorating healthcare conditions due to its political context.

The shared challenge across these countries is to guarantee healthcare access for all citizens — particularly in rural areas — through a well-coordinated network of regional hospitals, local health centers, and community health workers. A sufficient number of doctors and healthcare staff must be trained and deployed across the entire territory with appropriate equipment and reliable laboratories. Community health workers play a crucial role in the most isolated villages, so ensuring their fair compensation is essential.

What factors can challenge universal access to healthcare?

Pricing is a key consideration. Equality in healthcare access is paramount. Thailand — and to a lesser extent, Vietnam — have such top-tier healthcare infrastructures that the country is witnessing a surge in medical tourism; private care may certainly be cheaper than in Europe, it remains out of reach for most of the population. Ensuring free healthcare services, of quality, and accessible to rural residents is essential. However, this has a significant cost for the Ministry of Health, necessitating continued international aid.

In combating HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis, as well as addressing the taboo surrounding mental health issues that persist in the region, it is vital to fight against patient stigmatization: those who feel ashamed of their condition may hesitate to seek treatment, potentially exacerbating its spread. Once again, the pivotal role of community agents in conveying crucial messages is emphasized.

How can international assistance best support these countries?

Currently, we are witnessing a shift in international aid towards other countries with more urgent needs, leaving the Greater Mekong countries to navigate declining aid. Nevertheless, nations in the region, notably Cambodia and Laos, still require substantial assistance to maintain their vigilance against major pandemics. The goal is not to replace the Ministries of Health of the countries involved, but rather to initiate pilot projects, as we have done with the support of L’Initiative, focusing on malaria in forested areas in Cambodia. We highlight an issue by introducing a preventive and therapeutic approach, and if successful, we propose scaling it up to the government. As a frontline physician, this is where I find my usefulness.

Are additional resources needed for noncommunicable diseases and pandemics?

Certainly, the most cutting-edge treatments for diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, or cancer are very costly, often placing them out of reach for these nations. Addressing pandemics like COVID-19 require sending people to intensive care units, the expertise and equipment needed are also hefty. As a result, countries in the Greater Mekong region must carefully allocate funds, working with healthcare budgets per capita that are substantially below the global average.

Is it possible to utilize emerging technological tools to advance both research and healthcare accessibility?

Telehealth and artificial intelligence can serve as valuable diagnostic tools, particularly in the most isolated rural areas where qualified doctors may be far away but internet connectivity is widespread, it is best to take advantage of it. From a One Health perspective, these tools are also instrumental in facilitating the exchange and analysis of data among various professional groups (including veterinarians, ecologists, and physicians) to identify factors contributing to disease emergence. This represents a critical challenge, often overlooked by many ministries due to time constraints, and one where international collaboration could play a significant role in development.